northern europeans began to think of — or at least write about — themselves as individuals beginning in the eleventh century a.d. [pgs. 158, 160, and 64-67 – bolding and links inserted by me]:

“The discovery of the individual was one of the most important cultural [*ahem*] developments in the years between 1050 and 1200. It was not confined to any one group of thinkers. Its central features may be found in different circles: a concern with self-discovery; an interest in the relations between people, and in the role of the individual within society; an assessment of people by their inner intentions rather than by their external acts. These concerns were, moreover, conscious and deliberate. ‘Know yourself’ was one of the most frequently quoted injunctions. The phenomenon which we have been studying was found in some measure in every part of urbane and intelligent society.

“It remains to ask how much this movement contributed to the emergence of the distinctively Western view of the individual…. The continuous history of several art-forms and fields of study, which are particularly concerned with the individual, began at this time: auto-biography, psychology, the personal portrait, and satire were among them….

“The years between 1050 and 1200 must be seen…as a turning-point in the history of Christian devotion. There developed a new pattern of interior piety, with a growing sensitivity, marked by personal love for the crucified Lord and an easy and free-flowing meditation on the life and passion of Christ….

“The word ‘individual’ did not, in the twelfth century, have the same meaning as it does today. The nearest equivalents were *individuum*, *individualis*, and *singularis*, but these terms belonged to logic rather than to human relations….

“The age had, however, other words to express its interest in personality. We hear a great deal of ‘the self’, not expressed indeed in that abstract way, but in such terms as ‘knowing oneself’, ‘descending into oneself’, or ‘considering oneself’. Another common term was *anima*, which was used, ambiguously in our eyes, for both the spiritual identity (‘soul’) of a man and his directing intelligence (‘mind’). Yet another was ‘the inner man’, a phrase found in Otloh of Saint Emmeram and Guibert of Nogent, who spoke also of the ‘inner mystery’. Their vocabulary, while it was not the same as ours, was therefore rich in terms suited to express the ideas of self-discovery and self-exploration.

“Know Yourself

“Self-knowledge was one of the dominant themes of the age…. These writers all insisted on self-knowledge as fundamental. Thus Bernard wrote to Pope Eugenius, a fellow-Cistercian, about 1150: ‘Begin by considering yourself — no, rather, end by that….For you, you are the first; you are also the last.’ So did Aelred of Rievaulx: ‘How much does a man know, if he does not know himself?’ The Cistercian school was not the only one to attach such a value to self-knowledge. About 1108 Guibert of Nogent began his history of the Crusade with a modern-sounding reflection about the difficulty of determining motive:

“‘It is hardly surprising if we make mistakes in narrating the actions of other people, when we cannot express in words even our own thoughts and deeds; in fact, we can hardly sort them out in our own minds. It is useless to talk about intentions, which, as we know, are often so concealed as scarcely to be discernible to the understanding of the inner man.’

“Self-knowledge, then, was a generally popular ideal.”

_____

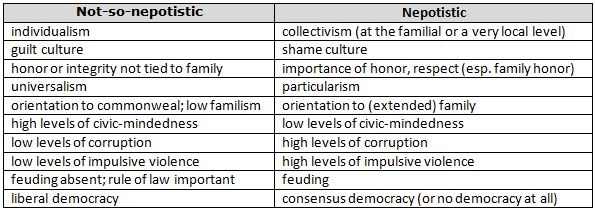

there seem to be two broad sociobiological/genocultural packages when it comes to average nepotistic vs. not-so-nepotistic altruistic behaviors in human populations — these are not binary opposites, but rather the ends of some sort of continuum of behavioral traits [click on table for LARGER view]:

the common thread running through the not-so-nepotistic groups of today (primarily northwest europeans) is a long history of outbreeding (i.e. avoiding close matings, like cousin marriage). (and a long history of manorialism. yes, i WILL start my series on medieval manorialism soon!) while individualism and guilt cultures may have been present in northern europe in paleolithic or even mesolithic populations, these behavioral traits and mindsets were definitely not present in the pre-christian germanic, british, or irish populations of late antiquity. those populations were very much all about clans and kindreds, feuding and honor, shame, and group consensus. guilt/individualistic cultures (i.e. not-so-nepostic societies) can come and go depending at least partly on long-term mating patterns. human evolution can be recent as well as aeons old.

the individualistic guilt-culture of northwest (“core”) europeans today came into existence thanks to their extensive outbreeding during the medieval period (…and the manorialism). the outbreeding started in earnest in the 800s (at least in northern france) and, as we saw above, by 1050-1100 thoughts on individualis began to stir. around the same time, communes appeared in northern italy and parts of france — civic societies. violence rates begin to fall in the 1200s, especially in more outbred populations, i would argue (guess!) because the impulsive violence related to clan feuding was no longer being selected for.

by the 1300-1400s, after an additional couple hundred years of outbreeding, the renaissance was in full swing due to the “wikification” of northern european society — i.e. that nw europeans now possessed a set of behavioral traits that drove them to work cooperatively with non-relatives — to share openly knowledge and ideas and labor in reciprocally altruistic ways. the enlightenment? well, that was just the full flowering of The Outbreeding Project — an explosion of these not-so-nepotistic behavioral traits that had been selected for over the preceding 800 to 900 years. individualism? universalism? liberal democracy? tolerance? reason? skepticism? coffeehouses? the age of enlightenment IS what core europeans are all about! hurray! (^_^) the Project and its effects are ongoing today.

it could be argued that the fact that certain mating patterns seem to go together with certain societal types is just a coincidence — or that it’s the societal type that affects or dictates the mating patterns. for example, i said in my recent post on shame and guilt in ancient greece that:

“shame cultures are all tied up with honor — especially family honor. japan — with its meiwaku and seppuku — is the classic example of a shame culture, but china with its confucian filial piety is not far behind. the arabized populations are definitely shame cultures with their honor killings and all their talk of respect. even european mediterranean societies are arguably more honor-shame cultures than guilt cultures [pdf].

“if you’ve been reading this blog for any amount of time, you’ll recognize all of those shame cultures as having had long histories of inbreeding: maternal cousin marriage was traditionally very common in east asia (here’re japan and china); paternal cousin marriage is still going strong in the arabized world; and cousin marriage was prevelant in the mediterranean up until very recently (here’s italy, for example).”

perhaps, you say, the causal direction is that nepotistic, clannish shame-cultures somehow promote close matings (cousin marriage or whatever). well, undoubtedly there are reinforcing feedback loops here, but the upshot is that both ancient greece and medieval-modern europe clearly illustrate that the mating patterns come first. (possibly ancient rome, too, but i’ll come back to that another day.) the pre-christian northern european societies were clannish shame-cultures until after the populations switched to outbreeding (avoiding cousin marriage) in the early medieval period. late archaic-early classical greek society was rather (a bit borderline) universalistic, individualistic [pg. 160+] and guilt-based until after they began to marry their cousins with greater frequency (at least in classical athens). the not-so-nepotistic guilt-culture we see now in northwest european populations is particularly resilient, i think, because the outbreeding has been carried out for a particularly long time (since at least the 800s) and thanks to the complementary selection pressures of the medieval manor system (which ancient greece lacked), but it did not exist before the early medieval period.

so, the direction of causation seems to be: (long-term) mating patterns –> societal type (nepotistic vs. not-so-nepotistic).

i think.

previously: there and back again: shame and guilt in ancient greece and big summary post on the hajnal line and individualism-collectivism

(note: comments do not require an email. earliest formal self-portrait, jean fouquet, 1450.)