(update 11/07/15: added a map and some comments to the third section below.)

if you’re a wise person who doesn’t fritter away their time on twitter, then you will have missed the short discussion the week before last about communism and east germany which was prompted by this tweet…

https://twitter.com/MaxCRoser/status/657871407918030848

as in the convos regarding russia and eastern europe in general which i mentioned in my last post, many tweeps attributed the very high rates of non-religious people in eastern germany versus western to that region’s years under communism. it was, in fact, this debate about east germany which reminded me that i had intended to post about the case of russia and civicness and corruption, etc. (which i then did!), but i wanted to address the matter of eastern germany in a separate post since there are several interesting nuances related to the question of europe’s east-west divide to be uncovered here which are particular to germany/central europe. (or at least i think they’re interesting!). so, here we go…eastern germany, medieval manorialism, and (yes) the hajnal line…

_____

again, just as in the case of russia, in order to try to settle the debate about whether or not communism left any long-lasting effects on the behavioral patterns (and beliefs, in this case) of east germans, i think we should start by asking if there were any similar such differences between east and west germans before the gdr existed. if yes, then i’d say we could pretty quickly rule out the communist state as having been much of an influencing force. at the very least, that premise would start to look pretty shaky. another approach might be to check the actual history: did the powers that be of the gdr actually suppress religious belief during the forty or so years of its existence? let’s look at the latter question first.

the consensus among historians (as much as such a thing can ever exist) appears to be, no — for most of time that the gdr was in existence, the communist authorities were fairly tolerant of christianity under a system known as “church in socialism” (“kirche im sozialismus”). here from Eastern Germany: the most godless place on Earth by peter thompson:

“Different reasons are adduced for the absence of religion in the east. The first one that is usually brought out is the fact that that area was run by the Communist party from 1945 to 1990 and that its explicit hostility to religion meant that it was largely stamped out. However, this is not entirely the case. In fact, after initial hostilities in the first years of the GDR, the SED came to a relatively comfortable accommodation with what was called the Church in Socialism. The churches in the GDR were given a high degree of autonomy by SED standards and indeed became the organisational focus of the dissident movement of the 1990s, which was to some extent led by Protestant pastors.”

while it’s true that religious education was banned in schools, theology faculties remained open at the major universities — although spies were deployed into those departments (like everywhere else, i suppose). but, also…

“…the Protestant Youth Committees, with their open-minded and different approach, attracted large numbers of young people from outside the church as well as from within it. The ‘Open Youth Work’ carried on by some pastors was an especially powerful draw for disaffected youths.” [pg. 51]

…and…

“Throughout its existence, there was a continuity in the basic policy of the GDR *Kirchenbund* towards the GDR authorities, summed up by the phrase ‘church within socialism’, avoiding the extremes of total assimilation or outright resistance to the policies of the SED [socialist unity party of germany]. The policy was only possible, however, because the GDR authorities themselves were prepared to tolerate the existence of a church which was not fully integrated into the SED dominated system of ‘democratic centralism’…. This created a space for the development of a limited ‘civil society’ and the growth of political disaffection….” [pg. 100]

…and…

“[I]n the early years of the GDR the state had made moves to diminish the importance of church festivals by turning days such as Christmas Day and Good Friday into ordinary work days. This meant that only Christians who were prepared to declare their faith in public by asking for special permission for leave could take time off to go to church. The Christmas holidays were turned into ‘New Year holidays’, but more fanciful attempts to blot out Christmas by calling Christmas trees ‘end of year trees’ and the Christ Child the ‘Solidarity Child’ seem to have fallen by the wayside.

“At their midnight services on Christmas Eve, churches were always full. Werner Krusche says he will never forget the cathedral in Magdeburg overflowing, with around 5,000 people coming to the different services, despite the icy cold. Many among them were not even members of the church. ‘Why did they come?’, he asks. ‘Perhaps they themselves didn’t exactly know. Enough that they were there and joined the celebration.'” [pg. 74]

so although the state did exercise a lot of control over the churches in east germany, it didn’t impact much on the religiosity of the populace — at least not according to the historians.

_____

here, however, is more from thompson [my emphasis]:

“Another factor is that religion in eastern Germany is also overwhelmingly Protestant, both historically and in contemporary terms. Of the 25% who do identify themselves as religious, 21% of them are Protestants. The other 4% is made up of a small number of Catholics as well as Muslims and adherents of other new evangelical groups, new-age sects or alternative religions. The Protestant church is in steep decline with twice as many people leaving it every year as joining.”

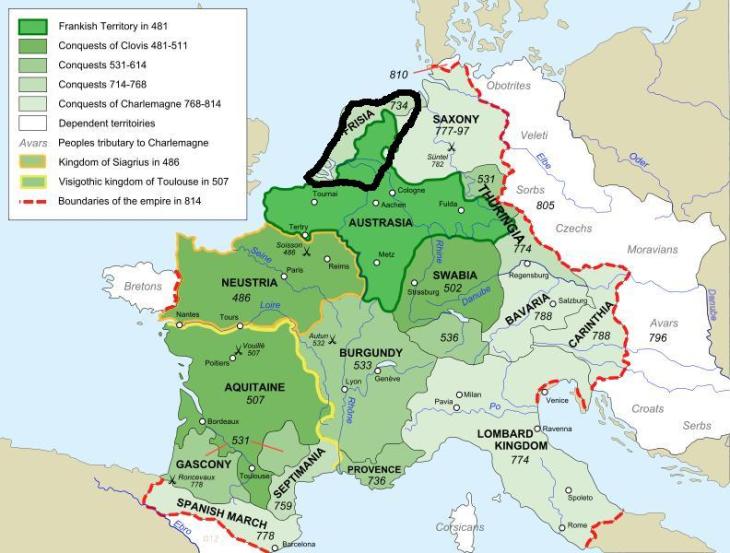

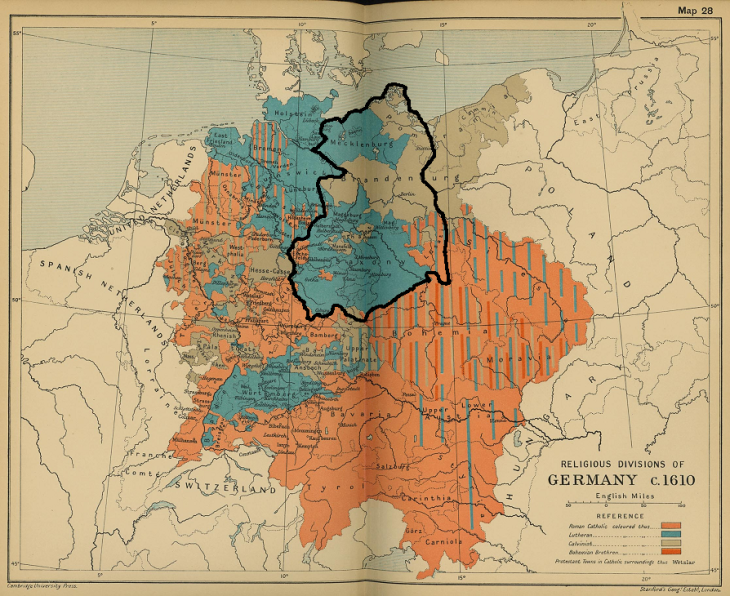

this brings us back to the first of my questions: were there any similar such differences between east and west germans before the gdr existed? and the answer is: yes, indeed. and precisely in the department of religion! jayman’s also previously pointed out that in the 1920s and 30s (north-)eastern germans voted quite differently than (south-)western germans. now we also have a religious divide — one that goes right back to at least the 1600s. here’s a map of the religious divisions in germany in 1610 (taken from here) on which i’ve attempted (*ahem*) to draw the borders of east germany [click on map to see a LARGER view]:

as you can see, in 1610 the vast majority of the population in the area that would centuries later become east germany was protestant (either lutheran or calvinist), and in general protestantism was more prevalent in the northern part of what is today germany than in the south. again, this is very much in accordance with what jayman blogged: that there’s a north-south as well as an east-west divide in germany.

edit (11/07):

following a suggestion by margulon who commented…

“One problem with your argument is that whether the reformation took long-term roots in a particular territory was not only decided by the local population within any territory of the Holy Roman Empire, but by the principle ‘cuius regio, eius religio.’ In other words, it was mainly the ruling princely family – members of a supra-regional elite – that decided about the religion in their respective territories according to their respective preferences. This also led to population exchanges of holdouts refusing to convert. I would therefore hesitate to draw conclusions from the predominant religion after 1648 or so.”

…here’s a map of the state of the reformation in germany from earlier in the period — 1560 — with the gdr outlined (roughly!) by me [map source — click on map for LARGER view]:

even as early as 1560, then, the region that would become east germany was almost entirely populated by protestants — mostly lutherans, but also some anabaptists. there doesn’t appear to be much of a calvinist population at this point, for whatever reason, unlike by 1610 (the map above). and again, on the whole, the northern parts of what would become germany had greater numbers of protestants than southern germany. the website from which i sourced this map, german history documents and images, says much the same:

“The map shows where the Reformation had been introduced by 1560. The most important areas lay in the Empire’s northern and central zones: Lutheranism in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Brandenburg, Braunschweig-Lüneburg, Hesse, Saxony, and (though outside the Empire’s boundary) Prussia. In the south, Lutheranism was established in Württemberg, parts of Franconia, and numerous Imperial cities. After c. 1580, the Catholic Church experienced a massive revival, which halted the advance of Protestantism and even allowed the old faith to recover some episcopal territories and most of the Austrian lands and the kingdom of Bohemia. Catholicism remained predominant in the western and southwestern portions of the Empire, including most of Alsace and all of Lorraine, as well as Bavaria. The third, Reformed confession spread via Geneva to France, the Netherlands, and some of the German lands. The outcome was a religious geography which survived both the demographic shifts caused by both the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) and the Second World War.”

end edit.

_____

the root cause behind these regional differences is not, i don’t think, simply religious or political or some other set of cultural practices, but rather lies in the recent evolutionary histories of these subgroups. as i said in my last post:

“the circa eleven to twelve hundred years since the major restructuring of society that occurred in ‘core’ europe in the early medieval period — i.e. the beginnings of manorialism, the start of consistent and sustained outbreeding (i.e. the avoidance of close cousin marriage), and the appearance of voluntary associations — is ample time for northwestern europeans to have gone down a unique evolutionary pathway and to acquire behavioral traits quite different from those of other europeans — including eastern europeans — who did not go down the same pathway (but who would’ve gone down their *own* evolutionary pathways, btw).

“what i think happened was that the newly created socioeconomic structures and cultural (in this case largely religious) practices of the early medieval period in northwest ‘core’ europe introduced a whole new set of selective pressures on northwest europeans compared to those which had existed previously. rather than a suite of traits connected to familial or nepostic altruism (or clannishness) being selected for, the new society selected for traits more connected to reciprocal altruism.“

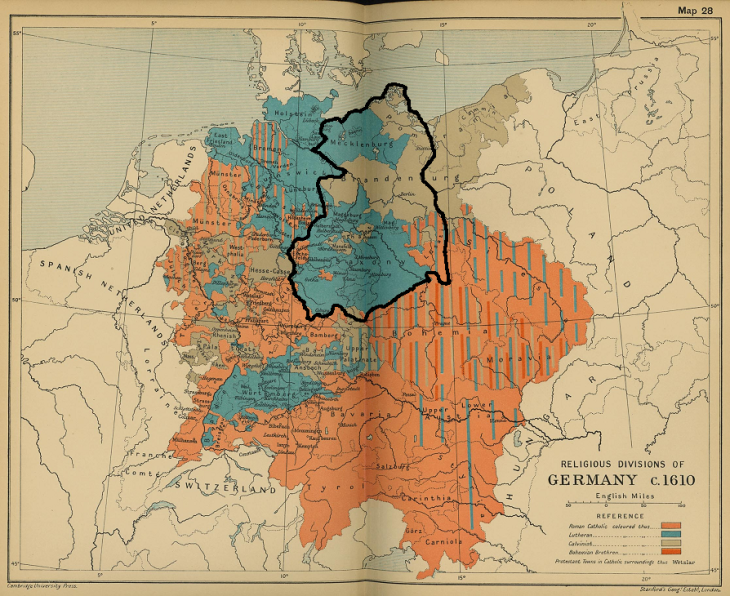

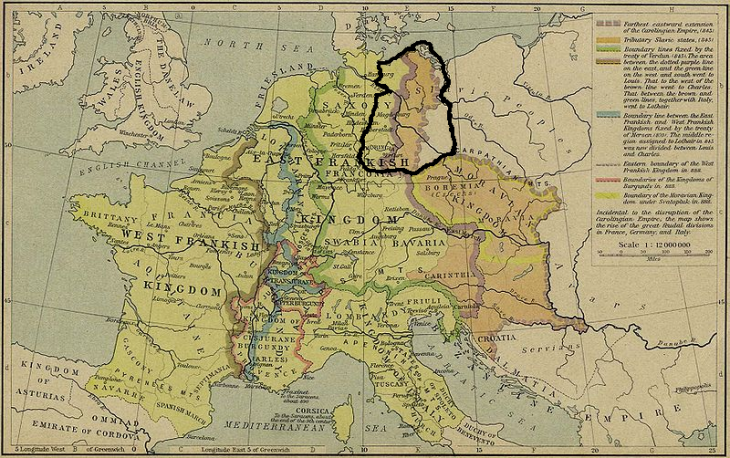

the “core” of “core” europe was the frankish kingdom of austrasia (from whence the pepinids or carolingians hailed), and this is both where the (bipartite) manor system originated in the 500s and where the avoidance of close cousin marriage (outbreeding) became de rigueur in the 800s. here’s a map indicating (as best as i could manage!) the austrasia of the 400s-800s as well as the much later gdr [click on map for LARGER view]:

most of east germany (the gdr) lies outside of the region formerly known as austrasia, as does large parts of both today’s northern and southern germany. southeast germany was incorporated into the frankish kingdom quite early (in the early 500s — swabia on the map below), but both northern germany and southwestern germany much later — not until the late 700s (saxony and bavaria on map). eastern germany, as we will see below, even later than that. the later the incorporation into the frankish empire, the later the introduction of both manorialism and outbreeding. and, keeping in mind recent, rapid, and local human evolution, that should mean that these more peripheral populations experienced whatever selective pressures manorialism and outbreeding exerted for shorter periods of time than the “core” core europeans back in austrasia. here’s a map of the expansion of the frankish kingdoms so you can get yourself oriented [source – click on image for LARGER view]:

in Why Europe?, historian michael mitterauer has this to say about the expansion of the frankish state and the spread of the manor system [pgs. 45-46 – my emphasis]:

“The most significant expansion of the model agricultural system in the Frankish heartland between the Seine and the Rhine took place toward the east. Its diffusion embraced almost the whole of central Europe and large parts of eastern Europe…. This great colonizing process, which transmitted Frankish agricultural structures and their accompanying forms of lordship…”

…not to mention people…

“…took off at the latest around the middle of the eighth century. Frankish majordomos or kings from the Carolingian house introduced manorial estates (*Villikation*) and the hide system (*Hufenverfassung*) throughout the royal estates east of the Rhine as well — in Mainfranken (now Middle Franconia), in Hessia, and in Thuringia…. The eastern limit of the Carolingian Empire was for a long time an important dividing line between the expanding Frankish agricultural system and eastern European agricultural structures. When the push toward colonization continued with more force in the High Middle Ages, newer models of *Rentengrundherrschaft* predominated — but they were still founded on the hide system. This pattern was consequently established over a wide area: in the Baltic, in large parts of Poland, in Bohemia, Moravia and parts of Slovakia, in western Hungary, and in Slovenia. Colonization established a line stretching roughly from St. Petersburg to Trieste….”

i think you all know what that line is by now. (~_^)

“The sixteenth century witnessed the last great attempt to establish the hide system throughout an eastern European region when King Sigismund II of Poland tried it in the Lithuanian part of his empire in what is now modern-day Belarus. The eastward expansion of Frankish agrarian reform therefore spanned at least eight centuries. The basic model of the hide system was of course often modified over such a long period, but there was structural continuity nevertheless.”

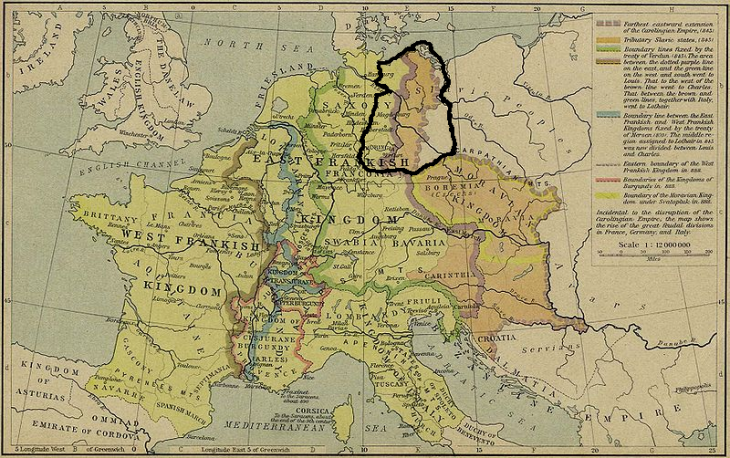

here’s a map of the carolingian empire between 843-888 [source] with the gdr (roughly!) indicated. from mitterauer again: “The eastern limit of the Carolingian Empire was for a long time an important dividing line between the expanding Frankish agricultural system and eastern European agricultural structures.” that “eastern limit” is the lilac border on the map, and as you can see something like two-thirds of what would become the gdr lay outside of that border [click on map for LARGER view]:

_____

in the earliest days of manorialism — back in austrasia in the 400-500s — manor life was a bit like living on a kibbutz — labor was pooled and everyone ate their meals together in the manor’s great hall. this was a holdover from the roman villa system which was run on the backs of slaves who lived in dormitories and were fed as a group by the owner of the villa. the manor system in core austrasia changed pretty rapidly (already by the 500s) to one in which the lord of the manor (who might’ve been an abbot in a monastery) distributed farms to couples for them to work independently in exchange for a certain amount of labor on the lord’s manor (the demesne). this is what’s known as bipartite manorialism. and from almost the beginning, then, bipartite manorialism pushed the population into nuclear families, which may for some generations have remained what i call residential nuclear families (i.e. residing as a conjugal couple, but still having regular contact and interaction with extended family members). over the centuries, however, these became the true, atomized nuclear families that characterize northwest europe today.

for the first couple (few?) hundred years of this manor system, sons did not necessarily inherit the farms that their fathers worked. when they came of age, and if and when a farm on the manor became available, a young man — and his new wife (one would not marry before getting a farm — not if you wanted to be a part of the manor system) — would be granted the rights to another farm. (peasants could also, and did, own their own private property — some more than others — but this varied in place and time.) over time, this practice changed as well, and eventually peasant farms on manors became virtually hereditary. (i’m not sure when this change happened, though — i still need to find that out.) finally, during the high middle ages (1100s-1300s) the labor obligations of peasants were phased out and it became common practice for farmers simply to pay rent to the manor lords. this is the Rentengrundherrschaft mentioned by mitterauer in the quote above. [see mitterauer for more details on all of this. and see also my previous post medieval manorialism’s selection pressures.]

so here we have some major differences in the selection pressures that western+southwestern versus eastern+northern+southeastern germans would’ve experienced in the early and high middle ages:

– western and southwestern germans of austrasia and swabia (see this map again) would’ve experienced both kibbutz-style and bipartite manorialism from very early on beginning in the 400-500s. contrasted with this, northern (saxony) and southeastern germans (bavaria) wouldn’t have experienced any sort of manorialism until after the late 700s at the earliest — three to four hundred years after the more western germans. so for a dozen or more generations, western germans (some of them would later become the french, of course) were engaged in bipartite manorialism, in which they had to delay marriage (if they wanted to take part in the system), and they were living in nuclear families.

– the region that would one day become east germany (the gdr) didn’t see any manorialism or nuclear families at all until germanic peoples (and some others) migrated to those areas during the ostsiedlung in the high middle ages, at least some six or seven hundred years after the populations in austrasia began experiencing these new selection pressures. and when manors were finally established there, they were based upon the rent system rather than being bipartite.

one important feature of the ostsiedlung — the migration of mostly germanic peoples from the west to central and parts of eastern europe — is that the subgroups of germanics from various regions in the west moved pretty much on straight west-to-east axes:

“As a result, the Southeast was settled by South Germans (Bavarians, Swabians), the Northeast by Saxons (in particular those from Westphalia, Flanders, Holland, and Frisia), while central regions were settled by Franks.”

so, the regions that would eventually become northern and east germany (the gdr) were populated by people not only from saxony (the one on the map above), who were a group late to manorialism and christianity (and, therefore, outbreeding), but also by people from places like frisia (and ditmarsia, iirc). i don’t know if you remember the frisians or not, but they never experienced manorialism. ever. and i suspect that the ditmarsians didn’t, either, but i’ll get back to you on that. (along with the peripheral populations of europe, there are other pockets inside the hajnal line where manorialism was weak or entirely absent, for example in the auvergne.) finally, the slavs (or wends) native to northern and eastern germany would not have been manorialized in the early medieval period, and most likely would’ve still been living in extended family groups, so any incorporation of slavs into communities newly settled by the germans (either by marriage or just direct assimilation of slavic families) would’ve again amounted to introgression from a population unlike that of the austrasian germans.

to conclude, when east germany was eventually settled by germanic peoples in the high middle ages, it was comparatively late (six or seven hundred years after the germans in the west began living under the manor system); the manor system in the region was not of the bipartite form, but rather the more abstract rental form; and the migrants consisted primarily of individuals from a population only recently manorialized or never manorialized. in other words, the medieval ancestors of today’s east germans experienced quite different selection pressures than west germans. so, too, did northern germans on the whole compared to southern germans. these differences could go a long way in explaining the north-south and east-west divides within germany that jayman and others have pointed out.

_____

what does any of this evolutionary history have to do with the fact that eastern germans today are much less likely to be religious than western germans, or that greater numbers of northern germans voted for the nazi party in the inter-war years than southern germans?

in my opinion, the latter question is more easily answered — or speculated about (in an informed and educated sort-of way) — than the first one. since northern germans have a shorter evolutionary history of manorialism and nuclear families and even outbreeding (due to their later conversion to christianity), then they may very well be more clannish, or exhibit more nepotistic altruism, than southern germans who are descended from the austrasian franks. thus, nationalsozialismus — not the most universalistic of political philosophies — might’ve appealed. dunno. Further Research is Required™.

with regard to the religious differences, i’m not sure. but here’s something that i think i’ve noticed which may or may not be relevant. here’s a map of the religious divisions in europe at the time of the reformation (1555 – source) onto which i’ve (sloppily!) drawn austrasia and neighboring neustria which was swallowed up by austrasia early on (486). if you look away from peripheral europe (places like ireland, spain, italy, greece, russia), it looks to me as though the protestant reformation happened in the regions immediately surrounding austrasia/neustria — at least that’s where the protestant movements largely began:

i really don’t know what to make of this, and don’t have much to say about it right now, except to repeat myself: the “core” core europe region of austrasia (+neustria) experienced bipartite manorialism, outbreeding, and small family types for the longest period, beginning as early as the 500s (for the manorialism and small families — 800s for the beginning of serious outbreeding), whereas the regions bordering this “core” core would’ve done so for shorter periods of time (and they saw different forms of manorialism as well). and way out in peripheral europe, these “westernization” selection pressures were present for very, very short periods of time (for instance, manorialism barely arrived in russia in the modern period, and then it was of a very different form from that of western europe). for whatever reasons, the protestant reformation appears to have happened in the middle zone. and the middle zone is where the former east germany lies.

_____

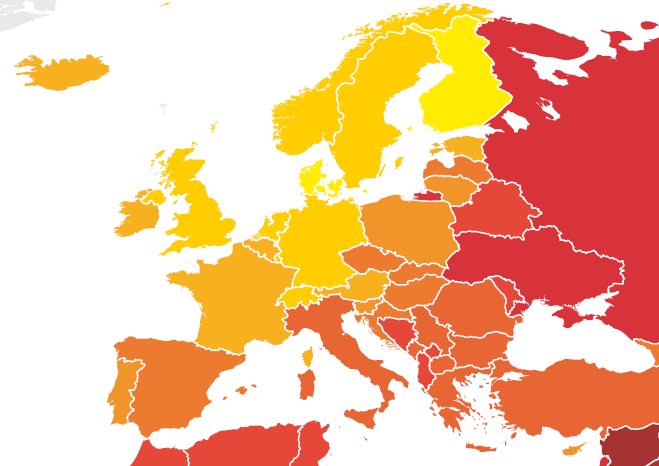

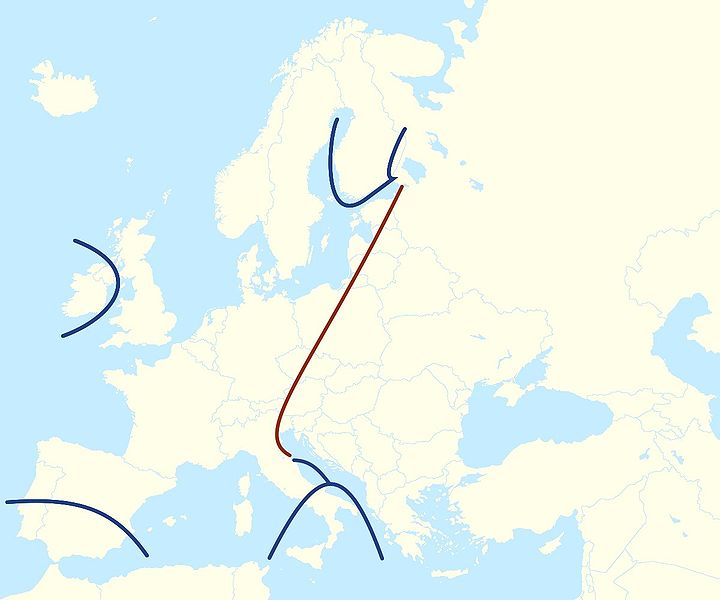

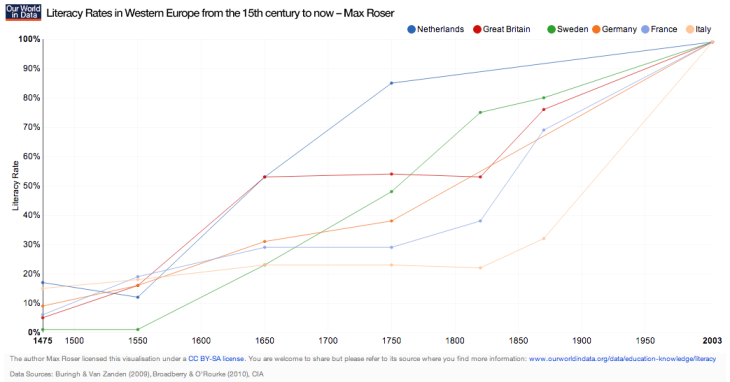

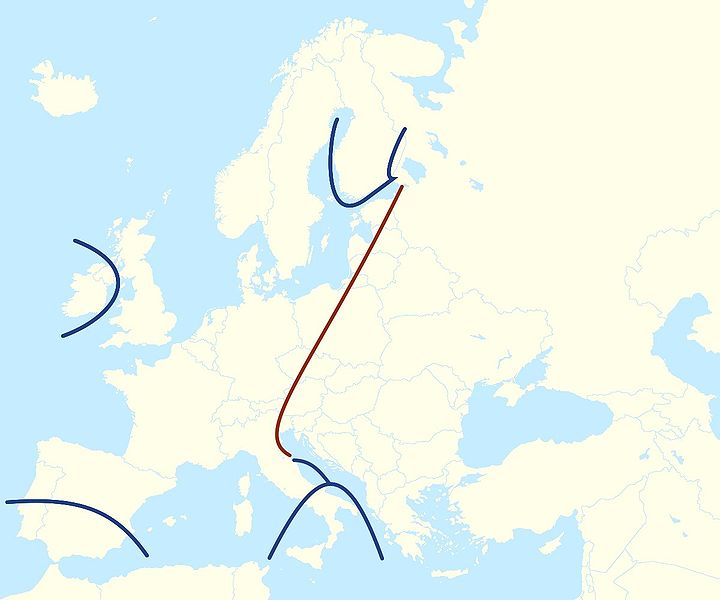

in 1965, john hajnal published his seminal finding that historically the populations of northwest europe were marked by late marriage — many even remained single — with a concomitant low birthrate. populations in eastern europe (and elsewhere) were not. the border between these two zones has become known as the hajnal line. subsequent research has found that other parts of peripheral europe — finland (parts of?), southern italy, the southern part of the iberian peninsula, and ireland — also lie outside the hajnal line:

michael mitterauer, who spent his career studying (among other things) the history of family types and structures from the middle ages and onwards, has connected the hajnal line to both the extent of bipartite manorialism and the western church’s precepts against cousin marriage. according to him, the hajnal line basically indicates where the bipartite manor system was present in medieval europe and where the cousin marriage bans were most stringently enforced — from the earliest point in time.

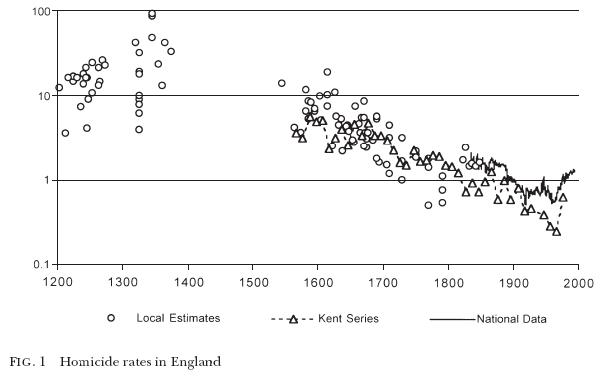

here on this blog, i’ve been posting about the apparent connection between the hajnal line and a whole slew of behavioral patterns and traits including (but very probably not limited to): family size, iq, human achievement, democratic tendencies, civicness, corruption, individualism (vs. collectivism), and even violence. see this post for more on all that: big summary post on the hajnal line. the primary factor connecting hajnal’s line to all these traits, i think, is the evolutionary histories of the populations found within and outside of the line. the basic outline of those different evolutionary histories is in the post above. “core” europeans and peripheral europeans vary in their average social behaviors thanks to the selective pressures they’ve experienced ever since the early middle ages, and the variances in those social behaviors impact many areas of those societies, from the highest levels of government and industry to everyday interactions between neighbors.

keep in mind that the hajnal line as indicated on the map above is schematic. it is NOT a perfectly straight line. the real border is fuzzy — a gradient, like most distributions of genes are (here’s lactase persistence in europe, for example). Further Research is Required™ to figure out where the border really is. also keep in mind that the hajnal line has no doubt been shifting over time, from west to east mainly, but also to the north and south, with the spread of manorialism from the “core” of core europe. that’s because human evolution can be recent, fairly rapid, localized…and is ongoing!

(^_^)

_____

footnote:

one issue which i didn’t take into consideration above is the possible effects of the post-wwii migrations on the population structure of east germany. to be honest with you, if it happened after 1066, my knowledge of it is usually kinda vague. (*^_^*) please, feel free to fill me in on the details of the modern migrations in the comments if you think they may have significantly affected the earlier population distributions. a couple of things that i do now know thanks to wikipedia are that: 1) four million germans entered east germany at the end of the war from east of the oder-neisse line; and 2) one quarter of east germans fled to the west between the end of the war and 1961. those are two very substantial migration/self-sorting events. with regard to those coming in from the east, presumably their evolutionary history would’ve been the same or very similar to the one i’ve just outlined for northern and eastern germans — late manorialism, Rentengrundherrschaft, later start of outbreeding, and late appearance of the nuclear family. and with regard to those east germans who fled to the west, given that one quarter migrated over the course of just fifteen or sixteen years, it wouldn’t surprise me if this had some effect on the average characteristics and behavioral traits of the remaining east german population. who left? who was left behind?

_____

postscript:

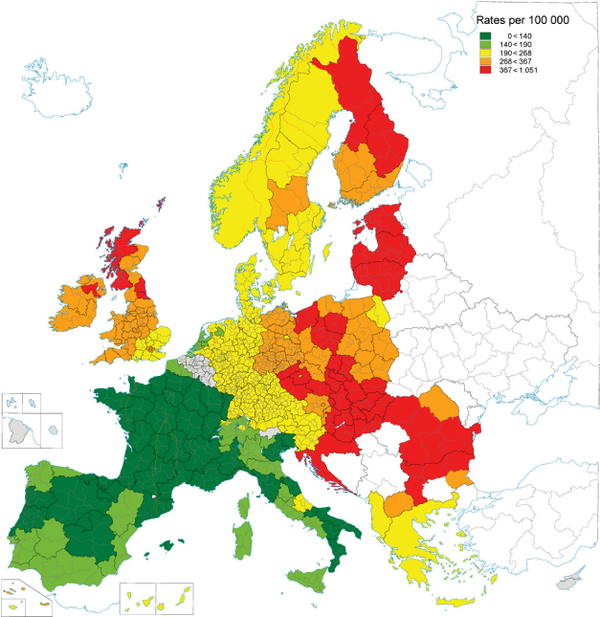

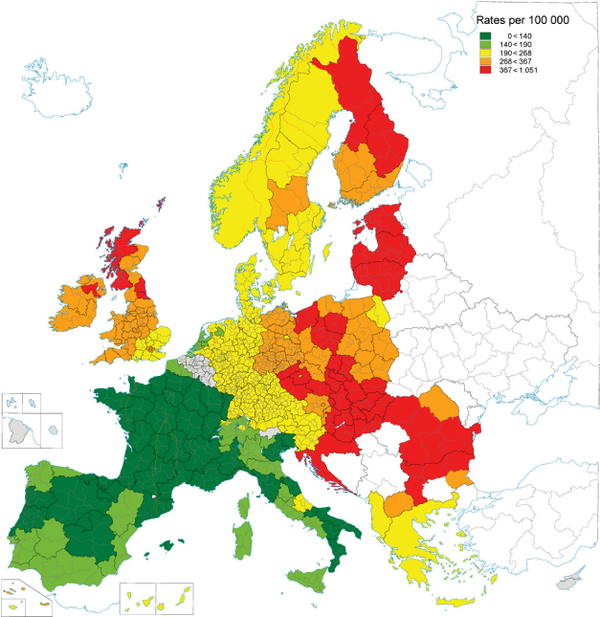

jayman tweeted this the other day — these are the cardiovascular mortality rates in european men from 2000:

his comment on this map was: “Great variation in the length of time peoples have had to adapt to agro pathogens.” you know what? i think this is exactly right. agro pathogens or, at least, agro something.

beginning in the early medieval period, northwest europe underwent an agricultural revolution. new grain crops were introduced — rye and oats (then, much later, wheat) — as well as some newfangled technological advancements (heavy plow, water mill). all of these spread through northern/western europe via manorialism. (see chapter 1 in mitterauer for more on all this.) i think you can see this dispersal on the map above. maybe.

italy and spain and parts of gaul would’ve grow wheat when they were a part of the roman empire, so those populations have been consuming wheat for quite a long time. they’re in the green with the lowest rates of cardiovascular mortality. the “founder crops” in europe — those that were introduced during the neolithic revolution from the middle east — were emmer (a two-grained spelt), einkorn (one-seeded wheat), barley, and naked wheat. these have been variously consumed in different parts of europe more or less since the neolithic (roughly speaking). the production of rye and oats (and again at a much later point modern wheat) was the mainstay of the manor system, and i think their arrival in different parts of europe is visible on the map above: france (austrasia) where manorialism started has the lowest rate of cardiovascular mortality (plus the population prolly also benefits from its agri-evolutionary history stretching back to roman days); then you see the spread of manorialism (and rye and oats) to the yellow zones — the advancement of the carolingian empire into central europe and also across the channel to southeast england (and to scandinavia?); east germany remains orange since it was manorialized later than western germany (see above post!) — same with northern and western england and ireland (which wasn’t manorialized until something like the 1400s); finally, eastern europe is in the red zone, “manorialized” (barely) very recently.

that looks like a good fit, but, of course, correlation doesn’t mean causation. (~_^)

_____

previously: community vs. communism and big summary post on the hajnal line and medieval manorialism’s selection pressures and mating patterns of the medieval franks

(note: comments do not require an email. down on the manor.)