speaking of viscous populations, large parts of eastern europe, beyond the hajnal line, have been characterized by extended families for a very long time, in contrast to northwestern “core” europeans.

here from karl kaser a map (probably roughly) showing both the limits of bipartite manorialism in europe (it didn’t extend into eastern europe) as well as the historic presence of nuclear vs. extended families between western and eastern europe. this map adds some of the squiggles to the hajnal line that i’ve been saying must exist — must be a fuzzy border in general:

so, west of that line (with some exceptions): bipartite manorialism going back to the 500s-800s (earlier the closer to the center of core europe), nuclear families going back to around that same time, and the avoidance of cousin marriage from around the 800s. east of that line: no bipartite manorialism, although some late “other” manorialism in northern eastern europe (i’ll explain that in my next post — there was never any manorialism in the balkans), extended families in many regions lasting right up until the present day (especially the balkans), and apparent late avoidance of cousin marriage compared to western europe — or, at least, not as strictly enforced for large parts of the medieval period.

all things considered, then, eastern european populations have been more viscous than northwestern ones for at least the last one thousand years.

in Power and Inheritance: Male Domination, Property, and Family in Eastern Europe, 1500-1900 [pg. 53+], karl kaser outlines how the differing economic and inheritance systems between eastern, western, and southern europe between 1500 and 1900 influenced family types. (and the foundations of these different systems stretch back into the medieval period.) i’m not going to get into all the details here, but, again, thanks to the socio-economic structures found in these three regions of europe, eastern populations wound up being more viscous than those in the west, and southerners some weird hybrid in between the other two. (but, quite possibly, the southern italians have had a higher cousin marriage rate than eastern europeans.) here from kaser [my emphases]:

“The inheritance geography of Europe can be roughly divided into three large areas: Western, Eastern, and Mediterranean zones, each with its own variations. Omnipresent, of course, is the potential for administrative intervention to change the customary laws of inheritance, whether for purely economic or even military purposes. Two basic variants, the *Grundherrschaft* system and that of a tributary system, can be distinguished. The exclusive goal of the tributary systems was to force the peasant families to pay their taxes and fees and fulfill their labor obligations vis-a-vis the landlords, while the *Grundherrschafts*-system enabled the landlord to intervene in questions of inheritance, family organization, and landed property. Europe had *Grundherrschaft*-systems in Central and Western Europe, while various forms of tributary systems were most characteristic of Eastern and Mediterranean Europe. In addition, we have to consider whether or not agnatic structures played a decisive role. Where the agnatic ideology was crucial, inheritance usually was considered patrilineal property of the group and was controlled by the group. In regions where the role of the agnatic group was weak or nonexistent, inheritance procedure focused on the conjugal couple and the nuclear family. Thus we have additionally to differentiate agnatically (with the focus on the descent group) and conjugally oriented areas (with the focus on the nuclear family). Eastern Europe belonged to the first; Western and Mediterranean Europe, with the exception of the larger islands — Sardinia, Corsica, Sicily, Crete, and Cyprus — belonged to the second. The Mediterranean area, dominated by tributary systems, was conjugally oriented….

“In the Mediterranean, there exists a long tradition of equally partible inheritance, the tributary system, and the relative absence of patrilineal descent concepts with the nuclear family as the primary social unit. In Western Europe, the result was the same, but the reasons and contexts were different….

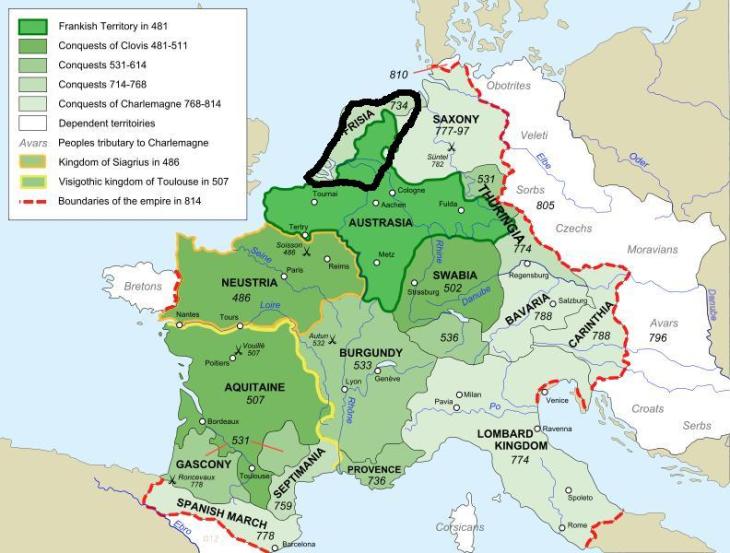

“The Western and Central European pattern of unigeniture, the right of succession to the impartible inheritance of land and nuclear family on the farmstead, developed in two phases. It originated during the 7th and 8th centuries in the Frankish kingdom, the territory of which covered large parts of Central and Western Europe, before Charlemagne came to power. In the second phase, between the 11th and 14th centuries, this inheritance pattern was extended eastward in the course of a massive colonization of conquered territories by *Grundherrn* and their peasants. They first reached the Elbe and then moved eastward. Thus an important zone of cultural transition was established. This zone not only divided two marriage patterns but also different systems of inheritance and household formation….”

and, crucially, these different systems set up different selection pressures.

“It divides the *Grundherrschaft* system from tributary systems, conjugal — from agnatic-centered systems, and systems of impartible inheritance from those with equally partible male inheritance….”

see here for more on this process.

“In territories east of the transition zone, tributary systems were almost never replaced by *Grundherrschaft* systems, and thus inheritance followed traditional patrilineal customary laws until the 19th and early 20th centuries. In the wide plains of Eastern Europe, large feudal estate were established on tributary lines….

“It is interesting that the inheritance systems in Bohemia and Moravia — in what today constitutes the Czech Republic, on the one hand, and in the Slovak Republic, which was part of Hungary until 1918, on the other hand — were completely different. Bohemian customary law had provided for equal male partible inheritance, but this was replaced by the new German law brought with colonization. Slovakia was only colonized in the form of isolated settlements, and the traditional system, which was even adopted by several German settlements, survived.

“The Polish kingdom formally introduced the German legal system and the agrarian system of *Hufenverfassung* (based on the *Hufe* — the *manus* or hide — as the standardized concept for a peasant holding) throughout the country after colonization, despite the fact that colonization itself only reached western Poland. This introduction was successful in western Poland; and in the core area of Lithuania, the *Hufenverfassung* was also introduced and the land systematically redistributed. But in the eastern parts of the Polish-Lithuanian state, including Belarus and the Ukraine, male partible inheritance and strong agnatic communities survived. A considerable portion of the Baltic region was also affected by German colonization. Prussia was colonized by German settlers and landlords, and the agrarian structure of Kurland, Livonia, and Estonia was reorganized by German feudal lords who introduced impartible inheritance….

“It has already become clear that the tributary systems allowed the people to practice their traditional inheritance practices. The same was true with household arrangements. The system of equally partible male inheritance offered several variants for property transfer: Transfer might not have been part of every individual life-course, in which case a large and complex household could emerge; it could systematically carried out upon the marriage of sons, which would have a system of nuclear families as its consequence; or it could be carried out after a certain period of marriage, e.g., upon the death of the father, and the individual life-course would experience phases of both nuclear and complex family constellations….

“The household formation patterns in the rest of Eastern Europe [i.e. outside of the balkans] cannot be defined this clearly — but were nonetheless analogous, in that they, too, were based on male partible inheritance and in the fact that the household was the primary working unit. The societies of Eastern Europe had no servants on the farmsteads….”

_____

so, again, i think there are at least three things to juggle in our heads here when thinking about possible selection pressures for nepotistic (or or not-so-nepostistic) altruism, all having to do with the “viscosity” of populations: 1) inbreeding, 2) family types, and 3) the forces socio-economic systems exert on familial relationships. for more than the last thousand years, northwestern european pops have had low inbreeding, small family types, and societal pressures which have pulled apart related individuals (those pressures increased over the period). eastern european pops have probably had higher inbreeding for some or all of this time period (although nothing on the scale of the arab world), large family types, and not very many social or economic pressures for family member to disperse. the mediterranean world, aside from the large islands mentioned by kaser above, has had higher inbreeding rates than northwestern europe (especially southern italy), small family types (at least, small residential family types), but few pressures for close family to separate much.

that’s all i’ve got for you for now. i WILL be coming back to this! (^_^)

previously: viscous populations and the selection for altruistic behaviors and family types and the selection for nepotistic altruism and “l’explication de l’idéologie” and big summary post on the hajnal line

(note: comments do not require an email. traditional family systems of europe.)