in a brief article on the church’s role in the development of things like political liberty (belated happy magna carta day, btw!) and prosperity in medieval england, ed west says:

“Last week I was writing about Magna Carta and how the Catholic Church’s role has been written out, in particular the part of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Stephen Langton.

“But the same could also be said about much of English history from 600AD to 1600; from the very first law code written in English, which begins with a clause protecting Church property, to the intellectual flourishing of the 13th century, led by churchmen such as Roger Bacon, the Franciscan friar who foresaw air travel.

“However, the whitewashing of English Catholic history is mainly seen in three areas: political liberty, economic prosperity and literacy, all of which are seen as being linked to Protestantism.

“Yet not only was Magna Carta overseen by churchmen, but Parliament was created by religious Catholics, including its de facto founder, Simon de Montfort….

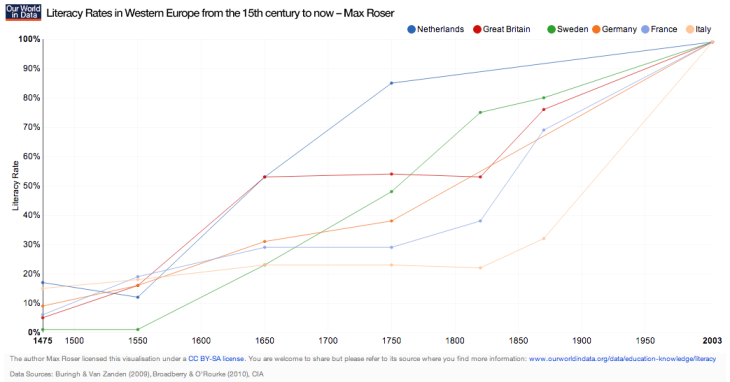

“Likewise literacy, which hugely increased in the 16th century and is often attributed to the Protestant attachment to the word, was already increasing in the 15th and the rate of growth did not change after Henry VIII made the break with Rome….”

here’s the graph from max roser on literacy rates in western europe from the fifteenth century onwards [click on chart for LARGER view]:

and more from ed west:

“As for the economy and the ‘Protestant work ethic’, well the English economy was already ‘Protestant’ long before the Reformation.

“‘By 1200 Western Europe has a GDP per capita higher than most parts of the world, but (with two exceptions) by 1500 this number stops increasing. In both data sets the two exceptions are Netherlands and Great Britain. These North Sea economies experienced sustained GDP per capita growth for six straight centuries. The North Sea begins to diverge from the rest of Europe long before the “West” begins its more famous split from “the rest”. [W]e can pin point the beginning of this “little divergence” with greater detail. In 1348 Holland’s GDP per capita was $876. England’s was $777. In less than 60 years time Holland’s jumps to $1,245 and England’s to 1090. The North Sea’s revolutionary divergence started at this time.’

“In fact GDP per capita in England actually decreased under the Tudors, and would not match its pre-Reformation levels until the late 17th century.”

so there are three big things — political liberty, prosperity, and literacy — all of which improved significantly, or began on a trajectory to do so, already by the high middle ages in northwestern or “core” europe (england, netherlands, nw france, ne germany, scandinavia, etc.).

there are additionally some other large and profound societal changes that occurred in core europe which also started earlier than most people think:

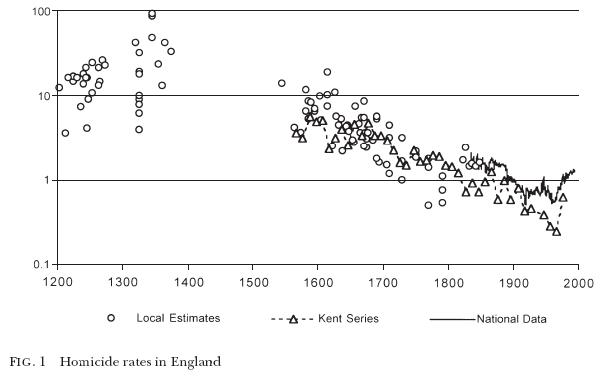

– a marked reduction in homicide rates, which has been studied extensively by historians of crime like manuel eisner, was written about at great length by steven pinker in his Better Angels, and most recently was suggested by peter frost and henry harpending to be the result of genetic pacification via the execution of criminals in the middle ages (i think they’re partly/mostly right!).

here’s the example of england (from eisner 2001):

“In the thirteenth and fourteenth century, the mean of almost 40 different estimates lies around 24 homicides per 100,000. The average homicide rates are higher for the late fourteenth century than for the thirteenth century, but it seems impossible to say whether this is due to the difference of the sources used or reflects a real increase related to the social and economic crises in the late Middle Ages. When estimate start again after a gap of some 150 years, the average calculated homicide rates are considerably lower with typical values of between 3-9 per 100,000. From then onwards, the data for Kent line up with surprising precision along a straight line that implies a long-term declining trend for more than 350 years.” [pg. 622]

while it is likely that the state’s persistent execution of violent felons over the course of a couple of hundred years in the late medieval/early modern period resulted in the genetic pacification of the english (and other core europeans — this is the frost & harpending proposal), it is also apparent that the frequency of homicides began to drop before the time when the english state became consistent and efficient about its enforcement of the laws (basically the tudor period) — and even before there were many felony offences listed on the books at all. homicide rates went from something like 24 per 100,000 to 3-9 per 100,000 between the 1200s and 1500s, before the state was really effective at law enforcement [pg. 90]:

“As part of their nation-state building the Tudors increased the severity of the law. In the 150 years from the accession of Edward III to the death of Henry VII only six capital statutes were enacted whilst during the next century and a half a further 30 were passed.”

the marked decline in homicides beginning in the high middle ages — well before the early modern period — needs also to be explained. you know what i think: core europeans were at least partly pacified early on by the selection pressures created by two major social factors present in the medieval period — outbreeding and manorialism.

– the rise of the individual, which began in northwest europe at the earliest probably around 1050. yes, there was a rather strong sense of the individual in ancient greece (esp. athens), but that probably came and went along with the guilt culture (pretty sure these things are connected: individualism-guilt culture and collectivism-shame culture). and, yes, individualism was also strong in roman society, but it seems to have waned in modern italy (probably more in the south than in the north, and possibly after the italian renaissance in the north?). siendentorp rightly (imho) claims that it was the church that fostered the individualism we find in modern europe, but not, i think, in the way that he believes. individualism can come and go depending, again i think, on mating patterns, and the mating patterns in northwest europe did not shift in the right direction (toward outbreeding) until ca. the 700-800s (or thereabouts) thanks to the church, so individualism didn’t begin to appear in that part of the world until after a few hundred years (a dozen-ish generations?) or so of outbreeding.

in any case, the earliest appearances of individualistic thinking pop up in nw europe ca. 1050, which is quite a bit earlier than a lot of people imagine, i suspect.

– the disappearance of and dependence upon the extended family — the best evidence of this of which i am aware comes from medieval england. the early anglo-saxons (and, indeed, the britons) had a society based upon extended families — specifically kindreds. this shifted beginning in the early 900s and was pretty complete by the 1100s as evidenced by the fact that members of the kindred (i.e. relatives) were replaced by friends and colleagues (i.e. the gegilden) when it came to settling feuds. (see this previous post for details: the importance of the kindred in anglo-saxon society.)

the usual explanation offered up for why the societies in places like iraq or syria are based upon the extended family is that these places lack a strong state, and so the people “fall back” on their families. this is not what happened in core europe — at least not in england. the importance of the extended family began to fall away before the appearance of a strong, centralized state (in the 900s). in any case, the argument is nonsensical. the chinese have had strong, centralized states for millennia, and yet the extended family remains of paramount importance in that society.

even in the description of siedentorp’s Inventing the Individual we read: “Inventing the Individual tells how a new, equal social role, the individual, arose and gradually displaced the claims of family, tribe, and caste as the basis of social organization.” no! this is more upside-down-and-backwardness. it’s putting the cart before the horse. individualism didn’t arise and displace the extended family — the extended family receded (beginning in the 900s) and then the importance of the individual came to the fore (ca. 1050).

there are a lot of carts before horses out there, which makes it difficult to get anywhere: the protestant work ethic didn’t result in economic prosperity — a work ethic was selected for in the population first and, for various reasons, this population then moved toward even more protestant ideas and ways of thinking (and, voila! — the reformation. and the radical reformation as a reaction to that.) a strong state did not get the ball rolling in the reduction in violence in nw europe or lead to the abandonment of the extended family — levels of violence began to decline before the state got heavily involved in meting out justice AND the extended family disappeared (in northern europe) before the strong state was in place. and so on and so forth.

it’s very hard for people to truly understand one another. (this goes for me, too. i’m no exception in this case.) and, for some reason, it seems to be especially hard for people to understand how humans and their societies change. i suppose because most people don’t consider evolution or human biodiversity to be important, when in fact they are ALL important! in coming up with explanations for why such-and-such a change took place, the tendency is to look at the resultant situation in our own society — eg. now the state is important rather than the extended family, which is what used to be important — and to then assume that the thing characteristic of the present (the state in this example) must’ve been the cause of the change. i don’t know what sort of logical fallacy that is, but if it doesn’t have a name, i say we call it the cart-horse fallacy! (alternative proposal: the upside-down-and-backwards fallacy.) explaining how changes happened in the past based on the present state of affairs is just…wrong.

so, a lot of major changes happened in core european societies much earlier than most people suppose and in the opposite order (or for the opposite reason) that many presume.

_____

also, and these are just a couple of random thoughts, the protestant reformation happened in the “core” of core europe; the radical reformation (a set of reactionary movements to the main reformation) and the counter reformation (the more obvious reactionary movement to the reformation) happened in peripheral europe. the enlightenment happened in the “core” of core europe; the romantic movement, in reaction to the enlightenment, happened in peripheral europe (or peripheral areas of core countries, like the lake district in england, etc.). just some thoughts i’ve been mulling over in my sick bed. =/

_____

see also: The whitewashing of England’s Catholic history and The Church’s central role in Magna Carta has been airbrushed out of history from ed west. oh! and buy his latest kindle single: 1215 and All That: A very, very short history of Magna Carta and King John! (^_^)

previously: going dutch and outbreeding, self-control and lethal violence and medieval manorialism’s selection pressures and the importance of the kindred in anglo-saxon society and the radical reformation.

(note: comments do not require an email. back to my sickbed!)