jayman’s got a cool new post up on clannishness and western inventiveness! here are a few thoughts from me…

jayman said re. the abstract thinking type of westerners vs. the holistic thinking type of easterners (a la nisbett) [my emphasis]:

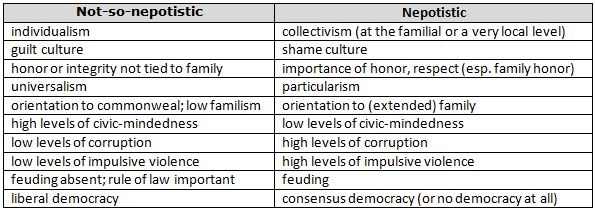

“[A]nother key difference between Western vs. Eastern (i.e., WEIRDO vs. clannish) thought: the former see things (and themselves) as atomized individuals, while the latter view objects in the world as part of an interconnected whole. This is a defining aspect on the clannishness dimension: low-clannishness peoples (WEIRDOs) see themselves as atomized individuals, who form associations voluntarily and not necessarily based on kinship. High-clannishness peoples see themselves as inherently part of the group (e.g., family, clan, tribe, village/town, etc.)….

“How did this penchant for abstraction come about among NW Europeans? I suspect that part of it has to do with the rise of high-trust and social atomization (i.e., individualism) in NW European societies. As clannishness disappeared, and as people were no longer bound to their families or clans (and indeed, we were free to interact with non-relative in cooperative ventures), people became more free to engage in intellectually stimulating thought. Mental space previously devoted understand one’s place in society and keep ahead of schemers now could be used on more abstract pursuits.“

while it’s an interesting idea, i don’t think that freed up mental capacity once dedicated to clannish traits was co-opted in the brains of westerners (nw europeans) in their post-clannishness state and then devoted greater abstract thought. maybe. but i suspect the connection is (somehow) much more direct: i think (theorize, speculate, etc.) that in simply becoming more independent individuals — i.e. less genetically like others around them thanks to outbreeding — that the mindset simply shifted. atomized individuals, atomized (and, therefore, abstract) thinking. please don’t get your panties all in a bunch. yes, this is complete and wild speculation on my part. i can’t even guess what the mechanism might have been, so don’t sue me if i’m wrong. (nw europeans, btw, began to think of themselves as individuals in the middle of the eleventh century a.d.)

another much more informed guess: that nw europeans’ exceptional ability for inventiveness especially in science (which cannot be divorced from their high average iqs — as jayman pointed out, africans are pretty inventive, but without enough iq points, no one there’s going to the moon) has a LOT to do with the selection pressures that happened thanks to the manor system which was found in nw europe during the middle ages, specifically bipartite manorialism.

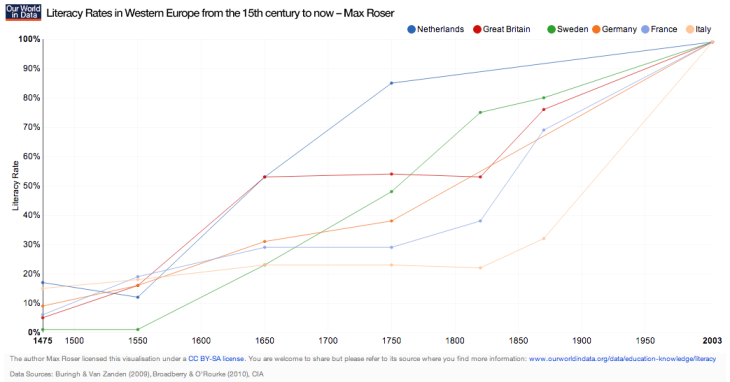

to back up for a sec: inventiveness/creativity/scientific reasoning in east asians, or the relative lack of it. jayman suggests that their tendency for holistic — and, therefore, not abstract — thinking hobbles east asians when it comes to inventiveness, etc. that, i think, makes a lot of sense. i do think, though, that the cochran-harpending idea of conformity in east asia (“nails hammered down”/low levels of adhd) also makes a lot of sense. the two ideas go well together, imho. wrt the “nails hammered down” hypothesis, my bet is that that selection process goes waaaay back. complex chinese civilization (that centered around the yellow river valley) is three or four thousands of years old. i think they’ve been hammering down the contrarians/independent thinkers there for a very long time. greg cochran has mentioned that the high-altitude adaptation of tibetans works better than those of other groups adapted to living in the clouds because the tibetan adaptations have been under selection for longer (even some acquired from the denisovans and/or other archaic humans?). i suspect that this is why conformism/lack of independent thinking is so strong in east asia: it’s been under selection there for a very long time. northwest europe’s civilization is obviously much, much younger.

now, to return to northwest “core” europeans: i strongly suspect their inventiveness/abstract thinking style/scientific thinking (and other behavioral traits, for that matter) were selected for thanks to the the following medieval trifecta:

– outbreeding (i.e. the abandonment of close cousin marriage) which meant that the selection for nepostic altruism was curbed since family members would no longer share so many “genes for altruism” in common (see: renaissances), PLUS individuals became “atomized” (therefore more abstract thinking arose, etc.);

– change in family types from extended to nuclear, which again would limit the selection for nepotistic altruism since individuals would interact more with non-kin than family;

– bipartite manorialism, which began in frankish territories in northeastern france/belgium and spread across nw and central europe in areas that are pretty much coterminous (prolly not coincidentally) with the hajnal line.

oh. and the ostsiedlung.

bipartite manorialism, in which tenant farmers would work for (later pay rent to) the head of a manor but also farm for themselves, operated as a sort-of franchise system in which the tenants on their individual farms had to make it or break it independently (i.e. without support from an extended family/clan, the dumber members of which would no longer be a drag on our independent farmers). there was, no doubt, cooperation between the tenant farmers which, once the outbreeding reduced the selection for nepotistic altruism, could’ve resulted in the selection for a more general, reciprocal altruism. but bipartite manorialism, i think, would’ve also selected for other traits like a propensity to be hard working, delayed gratification, and inventiveness: those individuals who came up with new ideas for improving their farming (or related) techniques could’ve bettered their place on the manor and been more successful reproductively.

chonologically, bipartite manorialism came first, arising out of the abandoned latifundia system in what had been roman gaul perhaps as early as the 500s. there also appears to have been pressure from very early on on these manors for nuclear families, so the reduction in family size may very well have come next. finally, the avoidance of cousin marriage came into full swing in the frankish territories in the 800s.

the final stage — at least as far as the medieval period goes — in the selection for “core” europeans was the ostsiedling: this was The Big Self-Sorting to the east of individuals who were already well underway to being outbred/manorialized in western germanic regions — in other words, they were well underway to being westernized as we know it. i don’t think it can be a coincidence that the heart of human accomplishment in western europe (which is also pretty much the heart of human accomplishment) is found in the manorialized regions of europe and very much where the ostsiedlung happened (see also here). my bet is that it was very much hard-working, innovative (especially, at the time, in agricultural/engineering techniques), high-achievers who went forth into the east during the medieval period. and they prospered and multiplied once they were there.

so that’s the picture as i see it so far. i reserve the right to change my mind/be utterly and completely wrong. (~_^)

_____

oh. wrt to thinking like a westerner (abstract/atomized) vs. thinking like an easterner (holistic/group), i still suspect that peripheral europeans (like me!) might think more like easterners (i.e. holistically) than northwest “core” europeans. dunno for sure, and i didn’t have enough data to confirm or refute this little idea, but i’m still hanging on to it for now. really wish an actual scientist would check it out.

_____

jayman also said [his emphases]:

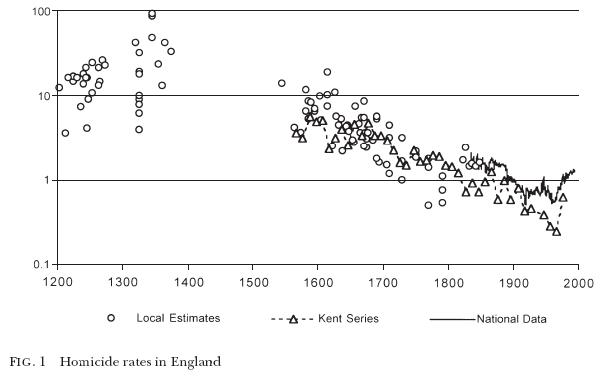

“The reality is that evolution proceeds much quicker than you think. Just as HBD’ers generally understand that human evolution didn’t stop 50,000 years ago, it also did not stop 10,000 years ago, or even 1,000 years ago, or even 500 or 200 years ago. Evolution continues right up to the present day. The reason I bring this up is because I keep hearing about how X group was doing this 2,000 years ago or about how Y group was doing this 1,000 years ago, so how could they be so different now? The reason is that they have changed since that time.“

hear, hear! and…duh! human evolution is recent, both global and local, ongoing, and can be pretty rapid. not in one generation, obviously, but twenty or forty is plenty of time. also, gene frequencies in populations move upwards or downwards over time — they do not (have to) remain stagnant. i quoted stephen stearns recently (here):

“Well I think what is very probably going on is that selection is moving a population up and down all the time. It goes off in a certain direction for a while, and then it goes back in the other direction. It’s only if you get a significant change in the environment that it will then continuously go in a new direction.”

and average differences in gene frequencies in populations is all you need for average differences in behavioral traits, etc. for example, i think the ancient greeks might’ve moved from a shame to a part-guilt and back to a shame culture again thanks (at least in part) to changes in mating patterns over the course of several hundreds of years. evolution does not have to be unidirectional.

_____

anatoly karlin said:

“Ancient Greeks did a lot of abstract thinking, and produced the greatest cultural/scientific peak until the Renaissance (according to the same Charles Murray’s figures). During the Middle Ages, in pure scientific terms, the Islamic world was most advanced. The Renaissance began in northern Italy. Only in the 17th century did the bulk of scientific discoveries move to NW Europe.”

as i mentioned above, it looks like the ancient greeks (the athenians) went from inbred to outbred and back to inbred again. mind you, i only have some pretty slim historic/literary evidence for that, so you should take my claim with a large grain of salt, but i’ll keep working on the Greek Question. the romans, who were also pretty sharp, at least when it came to engineering, were very clearly outbred (they bequeathed their outbreeding practices to us). the renaissance did begin in northern italy, and that doesn’t come as a big surprise to me ’cause northern italy was the most heavily manorialized part of italy (i’ll tell you more about this in my long overdue series on manorialism). northern italians were also prboably quite outbred during the medieval period, although further research is required on that front, too. the scientific revolution, however — especially the development of the scientific method — was very much a north european baby, though. from what i understand of science in the medieval islamic world, most of that was down to the persians. can’t tell you anything about medieval persian society, unfortunately, ’cause i don’t know anything about it.

that’s it. outta energy. more soon!

(note: comments do not require an email. De revolutionibus orbium coelestium.)