daniel hannan (Inventing Freedom: How the English-Speaking Peoples Made the Modern World) is full of admiration for the dutch (so am i!). here from a blogpost of his — I’ve realised why I like the Dutch so much: they invented capitalism — from the other day:

“Only recently, though, was I able to put my finger on what I liked so much. It’s this: for centuries, the Dutch made the honest pursuit of self-betterment a supreme virtue. Other European nations elevated honour and faith and martial glory, but the people Shakespeare called ‘swag-bellied Hollanders’ quietly got on with trade….

“I’ve just written a book about Anglosphere exceptionalism, published in the US next week and in Britain the week after. While writing, I couldn’t help noticing that one place had kept pace with the English-speaking peoples in the development of property rights, representative institutions, limited government and individualism. Indeed, on one critical measure, the Dutch beat us to it: modern capitalism, as defined by the twin concepts of limited liability and joint stock ventures, was invented in the Netherlands….”

meanwhile, in another corner of the internet, t.greer has been asking — and nicely answering! — a neat question: why the rise of the west? specifically, why in the middle ages did europe “diverge” from the rest of the world economically, never to look back? from Another Look at ‘The Rise of the West’ – But With Better Numbers (see also The Rise of the West: Asking the Right Questions):

“A few months ago I suggested that many of these debates that surround the ‘Great Divergence’ are based on a flawed premise — or rather, a flawed question. As I wrote:

“‘Rather than focus on why Europe diverged from the rest in 1800 we should be asking why the North Sea diverged from the rest in 1000.‘

“By 1200 Western Europe has a GDP per capita higher than most parts of the world, but (with two exceptions) by 1500 this number stops increasing. In both data sets the two exceptions are Netherlands and Great Britain. These North Sea economies experienced sustained GDP per capita growth for six straight centuries. The North Sea begins to diverge from the rest of Europe long before the ‘West’ begins its more famous split from ‘the rest.’

“[W]e can pin point the beginning of this ‘little divergence’ with greater detail. In 1348 Holland’s GDP per capita was $876. England’s was $777. In less than 60 years time Holland’s jumps to $1,245 and England’s to 1090. The North Sea’s revolutionary divergence started at this time.“

so, by the early 1400s, england and holland had taken off.

i’ve been in awe of the dutch golden age and the dutch during the renaissance/age of enlightenment (fwiw) in general (i love the art!).

why the dutch (and the english)? and why then? (you already know what i’m going to say….)

_____

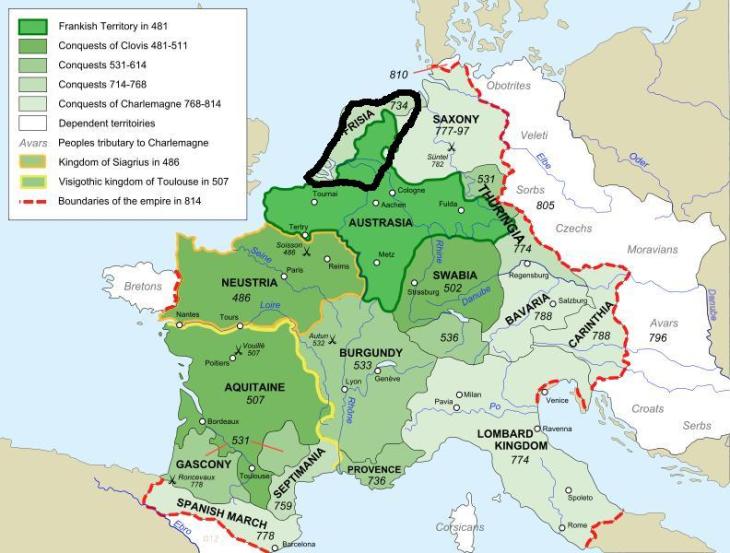

the netherlands — the low countries in general — were, once upon a time, a part of the early frankish kingdom of austrasia (i’ve more-or-less outlined the netherlands here — *ahem* — roughly):

the franks converted to roman catholicism early — in the late 400s — so they were positioned to adopt the church’s cousin marriage bans right away when they were instituted in the very early 500s (502 a.d.?), nearly one hundred years before the anglo-saxons in england. and there’s evidence that the franks did, indeed, adopt the cousin marriage bans early on — definitely by the late 500s (there’s always a lag time with these things). in fact, they seem to have taken pretty seriously all of the church’s marriage bans, including the ones regarding spiritual kinship (i.e. you couldn’t marry any of your godparents’ relatives because, since you were spiritually related to your godparents, you were also spiritually related to your godparent’s relatives). as i quoted in a previous post:

“St Boniface [d.754] expressed surprise when he learned that ‘spiritual kinship’ was created by lifting a child from the baptismal font and was being treated as an impediment to marriage among the Franks. But it was the law.”

The Outbreeding Project was so successful in franco-belgia and southern england that, by the 1300s, cousin marriage was a complete non-issue in the ecclesiastical courts in those regions.

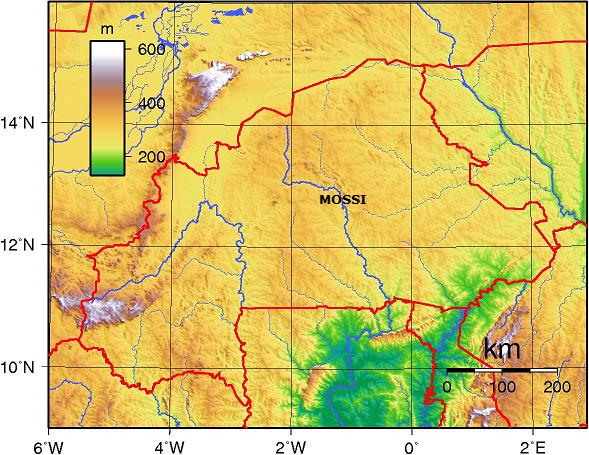

the exception in the low countries was the group of frisians along the coast who didn’t convert to christianity until the late 700s [pg. 11], so they were at least three hundred years behind the franks as far as The Outbreeding Project went.

in addition, the frisians went untouched by manorialism, which served to reinforce the cousin marriage bans as well as to push for nuclear families. and the frisians (like their coastal neighbors the ditmarsians) remained a bit wild and clannish until rather late in the medieval period. from michael mitterauer’s Why Europe? [pgs. 41-41 & 76]:

“The area settled by the Frisians along the North Seas coast is an interesting case from within the Frankish Empire itself. Manorial estates had not been established there — not by the king, the church, or the nobility — although the imperial heartland lay very close by. The reason for this may well be the ecological conditions that determined the economy. The region was admirably suited for grazing, so that agriculture faded into the background…. Natural conditions were lacking for the cerealization that had been implemented by Frankish neighbors. That a region in the Frankish Empire specializing in animal husbandry did not even begin to come close to establishing the bipartite estate confirms, e contrario, the belief in a connection between increased grain production and the rise of the manorial system. Nor was the agricultural system in Frisian settlements shaped later on by manorial structures. Very strong rural communal groups were established instead, placing the local nobles dispensing high justice in a percarious position….

“Ecological conditions might well have blocked the [hide] system’s progress in Friesland and the North Sea coastal marshes. It is striking that those are precisely the areas where we find features — such as the clan system and most notably blood revenge — that typify societies strongly oriented toward lineage. Blood revenge is rooted in a concept of kinship in which all men of a group are treated almost like a single person. The agnates together are considered to be the bearers of honor — and guilt. That is why the guilt of one relative can be avenged on someone else who had utterly no part in the deed. The idea of blood revenge is completely incompatible with Christian views of guilt and innocence. Nevertheless, the institution of blood revenge was still alive in several European societies even after they were Christianized, those in the North Sea marshes among them.”

the frisians were free!

_____

the dutch and the anglo-saxons are exceptional in terms of being individualistic (versus clannish) and, yet, oriented toward the commonweal — they’re both groups that developed capitalism and liberal democracy (perhaps the anglos are more fond of liberal democracy) — because these were the two populations in northwest europe that started outbreeding the earliest.

and now i’ve arrived back where i started two-and-a-half years ago (boy, will i ever shut up??) — with avner greif‘s paper Family Structure, Institutions, and Growth: The Origin and Implications of Western Corporatism [opens pdf]:

“There is a vast amount of literature that considers the importance of the family as an institution. Little attention, however, has been given to the impact of family structures on institutions, their dynamics, and the ability to change them…. This paper illustrates this by highlighting the importance of the European family structure in one of the most fundamental institutional changes in history.

“This change has been the emergence of economic and political *corporations* in late medieval Europe. ‘Corporations’ are defined here, consistent with their historical meaning, as intentionally created, voluntary, interest-based, and self-governed permanent associations. Guilds, fraternities, universities, communes and city-states are some of the corporations that dominated Europe in the past. Businesses and professional associations, business corporations, universities, consumer groups, republics and democracies are some of the corporations in modern economies.

“Providing institutions through corporations is a novelty. Historically, the institutions that secured one’s life and property and mitigated problems of cooperation and conflicts were initially provided by large kinship groups. Subsequently, such institutions that rely on this family structure were complemented or replaced by those provided by self-interested rulers. Corporation-based institutions can substitute for those provided by both kinship groups and self-interested rulers. When they substitute kinship-based institutions, corporations are complementary to a different family structure, namely, the nuclear family structure. For an individual, corporations reduce the benefits from belonging to a kinship group while a nuclear family increases the benefits from being a member of a corporation….

“[T]he actions of the Church caused the nuclear family — constituting of husband and wife, children, and sometimes a handful of close relatives — to dominate Europe by the late medieval period.

“The medieval church instituted marriage laws and practices that undermined large kinship groups. From as early as the fourth century, it discouraged practices that enlarged the family, such as adoption, polygamy, concubinage, divorce, and remarriage. It severely prohibited marriages among individuals of the same blood (consanguineous marriages), which had constituted a means to create and maintain kinship groups throughout history. The church also curtailed parents’ abilities to retain kinship ties through arranged marriages by prohibiting unions in which the bride didn’t explicitly agree to the union.

“European family structures did not evolve monotonically toward the nuclear family nor was their evolution geographically and socially uniform. However, by the late medieval period the nuclear family was dominate. Even among the Germanic tribes, by the eighth century the term family denoted one’s immediate family, and shortly afterwards tribes were no longer institutionally relevant. Thirteenth-century English court rolls reflect that even cousins were as likely to be in the presence of non-kin as with each other.

“The practices the church advocated, such as monogamy, are still the norm in Europe. Consanguineous marriages in contemporary Europe account for less than one percent of the total number of marriages. In contrast, the percentage of such marriages in Muslim, Middle Eastern countries, where we also have particularly good data, is much higher – between twenty to fifty percent. Among the anthropologically defined 356 contemporary societies of Euro-Asia and Africa, there is a large and significant negative correlation between Christianization (for at least 500 years) and the absence of clans and lineages; the level of commercialization, class stratification, and state formation are insignificant.”

in general, the dutch and the english have been outbreeding for the longest of all the europeans (of anybody, really), and they are two of the groups having the longest history of corporations in europe (there’s the northern italians, too), and they also have the strongest tendencies towards cooperative, voluntary, corporate groups today.

however, some of the dutch — and some of the english — actually did inbreed longer than some of the others: the frisians vs. the franks, the east anglians vs. the southeastern english. these groups were some of my in-betweeners — more outbred than your average arab, but less outbred than the longest of the long-term outbreeders. and the puritans (largely from east anglia) were big into business if Albion’s Seed is to be believed. and the frisians, too, were some of the earliest businessmen/traders in the low countries. from A Brief History of the Netherlands [pg. 15 – see also The Evolution of the Money Standard in Medieval Frisia: A Treatise on the History of the Systems of Money of Account in the Former Frisia (c.600-c.1500)]:

“Frisia (Friesland), however, remained a land apart. The Frisians were traders, stockbreeders, and fishermen, and feudalism took little hold in the swampy soil here.”

the combination of two not wholly dissimilar groups (franks+frisians, for instance), with one of the groups being very outbred (the franks) and the other being an in-betweener group (the frisians), seems perhaps to be a winning one. the outbred group might provide enough open, trusting, trustworthy, cooperative, commonweal-oriented members to the union, while the in-betweener group might provide a good dose of hamilton’s “self-sacrificial daring” that he reckoned might contribute to renaissances.

(and, yes, i am talking about the natural selection of innate behaviors.)

i could be wrong, but that’s my theory, and i’m sticking to it! (for now.) (^_^)

_____

p.s. – in case you’ve forgotten, the nations that saw the earliest reduction of homicides in the medieval period…yes…england and the netherlands/belgium: kinship, the state, and violence.

_____

previously: what about the franks? and trees and frisians and the radical reformation and whatever happened to european tribes?

(note: comments do not require an email. sunbathing giant sloth!)