the following are some very random thoughts/notions/questions/half-baked ideas about the reformation(s). just some things that i’ve noticed which may or may not mean something. thought i’d share. (^_^)

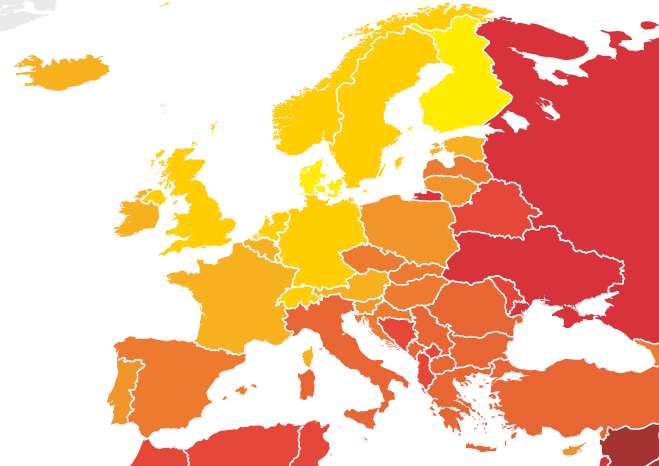

∎ i’ve mentioned this before, and i’m sure i’ll mention it again: to me, it looks like the reformation(s) occurred on the fringe of “core europe” (“core europe” being frankish austrasia/neustria where bipartite manorialism was first established and from whence it spread to other areas of western europe). why was there no (or comparatively little) reformation activity in the core of “core europe”? [the red line on the map below indicates the hajnal line which, if you don’t know what that is that by now…GET OFF MY BLOG! (~_^) the areas sloppily outlined in black are austrasia and, to its west, neustria.]

the pre-reformation era rebel christian groups that popped up were on the fringes: the waldensian movement began in southern france in the twelfth century, but really took root in the alpine border region between france and italy; the cathars of the same period were also from northern italy/southern france. john wycliffe came from a long line of yorkshiremen, and lollardism, having arisen in england in the mid-1300s, was also a movement located on the fringes of austrasia. even within england, lollardism seems to have had more of a following in areas that encircled “core england” — “core england” being where the manor system was first established (kent) and where the institution was most successfully implemented (the home counties).

the first proper set of of reformers — the hussites et al. that were a part of the bohemian reformation which began in the late-1300s — were from the kingdom of bohemia, nowadays the czech republic, so fringe (again, in relation to austrasia). luther was from eisleben in saxony, which later would be a part of east germany (the gdr), very much “fringe germany” — and lutheranism was, and is, very much a german/scandinavian thing, once again not occurring in the heart of “core europe.” calvinism is even more fringe than lutheranism, finding followers in scotland(!), among the frisians and dutch, the swiss, southwest france (the hugenots), and off in some parts of eastern europe — although calvin, himself, was from northern france. the radical reformation groups were even fringier.

why this pattern? (is it a pattern?!) why did the reformation (the reformations) arise around the edges of “core europe”?

∎ one of the main bugs of the reformers was, of course, what they viewed as the corrupt behaviors of the established church and clergy — the selling of indulgences, nepotism, usury — all that sort of thing. this was particularly the case for luther and his followers. it’s very clear that, today, northwestern “core” europeans are less corrupt than any of the peripheral europeans — southern europeans, eastern europeans, even (*gasp!) the irish:

was the reformation in germany the moment when an anti-corruption tipping point was reached in these northern populations? were corrupt, nepotistic behaviors simply largely bred out of these populations — via heavy outbreeding, heavy bipartite manorialization, and strong nuclear-family orientation for eight or nine hundred years — by this time? again though, if so, why wasn’t there a similar movement(s) in northeast france/belgium (austrasia) where these three factors (what i think were selection pressures) originated?

∎ the push for the publication of bibles in vernacular languages, and the widespread idea that there ought to be a personal/direct relationship between an individual and god, both strike me as expressions of individualism. again, individualism today is much stronger in northwest european populations than pretty much every other group on the planet, including in comparison to peripheral europeans. was an individualism tipping point reached in northwest european populations — thanks to selection for those traits — right around the time of the reformation? attitudes connected to individualism had already appeared in northern europe by the eleventh century, but perhaps the tipping point — the point of no return — was reached a couple of hundred years later.

∎ as i’ve said before, it seems to me that the calvinist ideas of predestination and double predestination are less universalistic than teachings in other versions of western christianity, including roman catholicism. roman catholicism is rather universalistic in the sense that everybody can be saved, but one does have to join the church (or at least you had to in the past) and repent, so the system is not fully universalistic. something like unitarian universalism is much more universalistic — almost anything and anyone goes. predestination/double predestination, wherein one is damned by god no matter what you do, sounds like some sort of closed, exclusive club. i don’t think it’s surprising that calvinism is found in peripheral groups pretty far away from “core” europe.

∎ the general animosity toward the centralized, hierarchical authority of the roman catholic church by those in the magisterial reformation, and their preference for working with more local, approachable authorities (eg. city councils), might possibly be seen as a rejection of authoritarianism on some level. that the members of the radical reformation rejected any secular or outside authority over their churches makes me think they’re rather clannish like scottish highlanders or balkans populations — generally not wanting to cooperate with outsiders at all.

∎ one of the biggest targets of the reformation in germany — one that, unlike the indulgences, etc., you don’t normally hear much about — is that the reformers wanted to take back control of marriage and marriage regulations from the central church. apart from the cousin marriage bans, another huge change that the roman catholic church had made to marriage in the middle ages was to make marriage valid only if the man and woman involved freely agreed to be married to one another. the church, in other words, had taken marriage out of the hands of parents who were no longer supposed to engage in arranging marriages for their children. the choice was to be freely made by the couple, no approval was necessary from the family, and, up until the 1500s, you didn’t even have to get married by a priest — two adults (a man and a woman) could just promise themselves in marriage to one another, even without witnesses, and that was enough. (one might always be disowned and disinherited, of course, if your parents didn’t approve, but they could not legally stop you from marrying.)

the germans reversed this after the reformation, and put marriage back in the hands of parents — at least they had to give their approval from then on. the reformers also reversed the cousin marriage bans, although curiously the rates of cousin marriage do not appear to have increased substantially afterwards.

i’m not sure how to characterize any of this. seems to be a bit anti-authoritarian and possibly individualistic. not sure. Further Research is RequiredTM. (^_^)

that’s all i’ve got for you today. the short of it is: i wonder if the reformations were a product of several tippining points in the selection for certain behavioral traits in northwestern europeans, among them individualism, universalism, and anti-corruption sentiments. and i don’t think the selection for any of these stopped at the reformation — northwest “core” europeans continued down that evolutionary pathway until we see at least one other big watershed moment in their biohistory: the enlightenment.

previously: the radical reformation and renaissances

(note: comments do not require an email. knock, knock!)