the dutch have been exceptional for quite a long time (see here, here, and here), and new york city (new amsterdam) inherited their exceptionalism. here’s colin woodard on “new york values” [kindle locations 144-150]:

“While short-lived, the seventeenth-century Dutch colony of New Netherland had a lasting impact on the continent’s development by laying down the cultural DNA for what is now Greater New York City. Modeled on its Dutch namesake, New Amsterdam was from the start a global commercial trading society: multi-ethnic, multi-religious, speculative, materialistic, mercantile, and free trading, a raucous, not entirely democratic city-state where no one ethnic or religious group has ever truly been in charge. New Netherland also nurtured two Dutch innovations considered subversive by most other European states at the time: a profound tolerance of diversity and an unflinching commitment to the freedom of inquiry. Forced on the other nations at the Constitutional Convention, these ideals have been passed down to us as the Bill of Rights.”

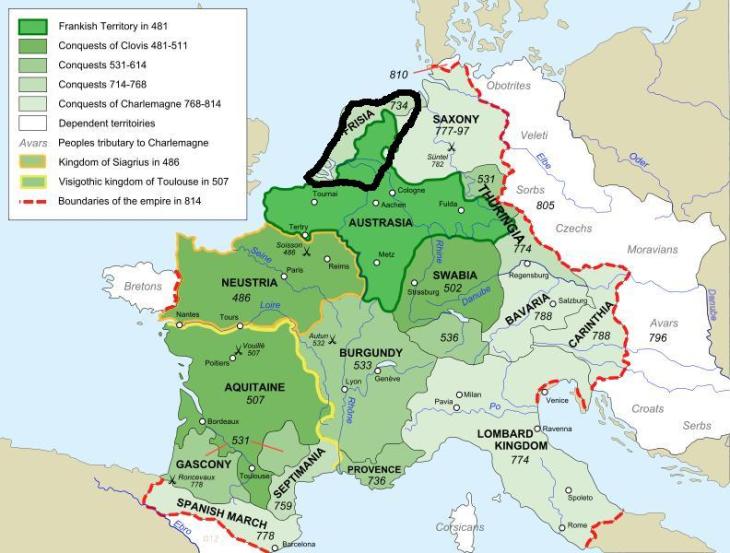

the dutch are located nearby, even half in, the heart of “core europe” — known as austrasia back in the day — the region in northwest europe where outbreeding (i.e. the avoidance of close cousin marriage), nuclear (not just residential nuclear) families, and manorialism all appeared earliest in the early medieval period (and maybe southeast england, too). here’s a map of the frankish kingdoms, including austrasia, with the location today’s netherlands (very sloppily) indicated (by me):

as you can see, the frisians are a bit of an exception — they were not a part of austrasia or the frankish kingdom until the 700s. i discussed the frisians in a previous post. apart from them, however, the dutch have been members of core europe since day one. why though do they seem to be not just core europeans but exemplary core europeans, what with their individualism and tolerance for diversity and their own northern renaissance and golden age? they’re really over the top core europeans. more core european in many ways than even the northern french who should, according to my outbreeding/manorialism theory, be super core europeans.

i really started to wonder about this when i read the other night that the netherlands was “very sparsely populated before 1500, and manorialism was of little importance.” huh?! i knew the frisians (like the ditmarsians) were never manorialized — that’s why they’re all a bit “wild” (i think) — but that wouldn’t make sense for the rest of the dutch. well, i think i’ve got it. and it turns out that the (evolutionary) history of the dutch is very interesting indeed!

to refresh everyone’s memory: manorialism — in particular bipartite manorialism — originated with the franks in austrasia probably in the 600s. here from michael mitterauer’s Why Europe? (which, if you haven’t read it by now, i might just have to ban you…) [pgs. 38-39 – this is mitterauer quoting another researcher]:

“‘I have introduced the concept of an early medieval ‘Frankish agrarian revolution’ that is implictly linked with the thesis that the…manorial village, field, and technical agrarian structures associated with this concept did not develop in Thuringia but were introduced as innovations — in a kind of ‘innovation package’ — from the western heartland of the Austrasian part of the empire…. I should like to reformulate my hypothesis thus: this type of agricultural reform was first put in motion in Austrasia around the middle of the seventh century, or somewhat earlier, under the Pippins, the majordomos of the Merovingians…. This innovation then caught on with nobles close to the king who in turn applied it to their own manorial estates. It would be most compelling to assume that the new model of the hide system — with its *Hufengewannfluren* and its large blocks of land (*territoria*) that were farmed in long strips (*rega*) — was also put into practice in the new settlements that were laid out by and for the kingdom (at the discretion of the majordomos) along the lines of a ‘Frankish state colonization.'”

mitterauer concurs and goes on to present much historic evidence showing how the frankish manor system was spread by the franks right across central europe over the course of a few hundred years (see also here). since “every society selects for something” — and since bipartite manorialism was a HUGE part of medieval northwest european society for something like six hundred years (depending on the region) — i’ve been trying to think through what selection pressures this manor system might have exerted on northwest “core” european populations (along with the outbreeding and the small family sizes — yes, there were undoubtedly other selection pressures, too). my working hypothesis right now: that, among other things, the manor system resulted in the domestication (self-domestication) of core europeans. more on that another day.

i’ve also been trying to work out which populations were manorialized when and for how long (along with how long they were outbreeding/focused their attentions on their nuclear families). for example, if you missed it, see here for what i found out about eastern (and other) germans.

now i’ve found out the story for the dutch. as i said above, the frisians were never manorialized. never, ever. which might account for why they’re, even to this day, a bit on the rambunctious, rebellious side. and up until the other evening, i thought the rest of the netherlands had been manorialized early on because it had been part of austrasia. but then i read that the netherlands was “very sparsely populated before 1500, and manorialism was of little importance.” *gulp!*

yes. well, what happened was: the netherlands was very sparsely populated before 1500, and there was, indeed, very little manorialism, but beginning in the 1000s, vast areas of peatlands in the netherlands (especially south hollad) were drained as part of large reclamation projects financed by various lords, etc. the labor was carried out by men who were then rewarded with farms in the reclaimed areas. much of this workforce was drawn from existing manors elsewhere in austrasia (in areas nearer to frisia, it would’ve been frisians doing the work/settling on the new farms). so inland netherlands, which was sparsely populated and where manorialism was not really present, was in large part settled by people from an already manorialized population. parts of austrasia had had manors since the 600s, and the reclamation projects began in the 1000s — and continued for a few hundred years — so that’s potentially 400+ years or so of manorialism that the settlers’ source population had experienced. thirteen generations or more, if we calculate a generation at a very conservative thirty years. some selection could’ve happened by then.

here from jessica dijkman’s Shaping Medieval Markets: The Organisation of Commodity Markets in Holland, C. 1200 – C. 1450 [pg. 12]:

“…the 11th to 13th centuries, when the reclamation of the extensive central peat district took place. The idea that the reclamations must have had a profound impact on the structure of society is based not only on the magnitude of the undertaking, but also on the way it was organised. Each reclamation project began with an agreement between a group of colonists and the count of Holland, or one of the noblemen who had purchased tracts of wilderness from the count for the purposed of selling it on. This agreement defined the rights and duties of both parties. The colonists each received a holding, large enough to maintain a family. In addition to personal freedom, they acquired full property rights to their land: they could use it and dispose of it as they saw fit. At the same time, the new settler community was incorporated into the fabric of the emerging state: the settlers accepted the count’s supreme authority, paid taxes, and performed military services if called upon….

“Jan de Vries and Ad van der Woude have suggested that in the absence of both obligations to a manorial lord and restrictions imposed by collective farming practices, a society developed characterised by ‘freedom, individualism and market orientation’. In their view this is part of the explanation for the rise of the Dutch Republic (with Holland as its leading province) to an economic world power in the early modern period. The argument seems intuitively correct, but the exact nature of the link between the ‘absence of a truly feudal past’ and marked economic performance at this much later stage is implied rather than explained.”

i’ll tell ya the nature of the link (prolly): biological — the natural selection for certain behavioral traits in the dutch population in this new social environment.

according to curtis and campopiano (2012), the reclamations and settlements in south holland were made “almost entirely on a ‘blank canvas’.” they also say that the reclamation projects [pg. 6]:

“…led to the emergence of a highly free and relatively equitable society…. In fact, the reclamation context led Holland to become one of the most egalitarian societies within medieval Western Europe…. In the Low Countries, territorial lords such as the Bishop of Utrecht or the Count of Flanders managed to usurp complete regalian rights over vast expanses of wasteland after the collapse of the Carolingian Empire in the tenth century. Rather than reclaiming these waste lands to economically exploit them directly, territorial lords looked to colonise these new lands in order to broaden their territorial area, thereby expanding their tax base.

“The consequences of this process were significant for large parts of Holland from the tenth century onwards. Both the Bishop of Utrecht and the Count of Holland lured colonists to the scarcely-inhabited marshes by offering concessions such as personal freedoms from serfdom and full peasant property rights to the land. The rural people that reclaimed the Holland peat lands between the tenth and fourteenth centuris never knew of the manor or signorial dues. In fact, many of the colonists in the Holland peat-lands originated from heavily manorialised societies and were looking to escape the constrictions of serfdom, further inland….”

i need to double-check, but i’m pretty certain that this is a quite different picture from what happened during the ostseidlung. while colonists to the east received their own farms, they still had signorial obligations (owed either labor or rents to the lord of the manor) — i.e. they were tied to manors for as long as the manor system lasted. that’s a different sort of society with different sorts of selection pressures for behavioral traits.

so the dutch — at least the dutch in holland (they *are* the dutch, aren’t they?!) — are descended from a population that spent 400+ years or so in a manor system, some of whom (self-sorting!) then jumped right in to a system where they were free and independent peasants working on their own and trading their wares in markets (another crucial part of the story…for another day). and they’ve been doing the latter for nearly one thousand years. well no wonder they invented capitalism (according to daniel hannan anyway)!

i still think that the combination of frisians+dutch/franks might’ve been the winning one leading to the enormous success of the tiny netherlands as i said in my previous post on the dutch. now, though, i would add manorialized/non-manorialized to that paragraph as well:

“the combination of two not wholly dissimilar groups (franks+frisians, for instance), with one of the groups being very outbred (the franks) and the other being an in-betweener group (the frisians), seems perhaps to be a winning one. the outbred group might provide enough open, trusting, trustworthy, cooperative, commonweal-oriented members to the union, while the in-betweener group might provide a good dose of hamilton’s ‘self-sacrificial daring’ that he reckoned might contribute to renaissances.”

previously: going dutch and trees and frisians and eastern germany, medieval manorialism, and (yes) the hajnal line and big summary post on the hajnal line and medieval manorialism’s selection pressures

(note: comments do not require an email. some hollanders.)

It occurred to me that the bulk of your readers are probably murkins, and that their land is much of it continental steppe. They might therefore have little intuition of how easily individuals could move about in maritime Europe. I was born in a small port in rural Scotland. My father told me I’d been bounced on Dutch and Norwegian knees before ever I’d met an Englishman. Similarly, within a twenty mile radius of my boyhood home there are place names of varied origin: British/Welsh, Roman, Anglo-Saxon, Norse, Danish, Gaelic, Norman French, Fleming, and doubtless some that predate any of these.

Maybe Phoenician ore prospectors passed through. Or Ancient Greeks from Marseilles. Who knows? Nobody expected the Spanish Armada, wisely as it turned out. It avoided us.

I can just about remember the Breton onion-sellers of my childhood, all bicycles and berets. Other exotic populations in my childhood included Italians, Ukrainians, and people who’d returned from India. Also Irish and Gypsies. Also also, the bastard offspring of Allied soldiers from The War.

Here we are.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Onion_Johnny

In a just world, you would be heralded by the press and academia as a visionary thinker who has developed a novel and exciting theory that explains the origin of modern cultures and peoples. Far sillier junk get more airtime, and by gods if anyone deserves it you do. But no, your brilliant theory and data sit languishing her in the dark corners of the innerwebs, waiting to be discovered and seen for what they are.

Maybe when you’re 90, you’ll finally get your due. Then I can say I knew you when.

(another crucial part of the story…for another day) Please get to this as quick as you can. Have always been fascinated by the non-feudal capitalist elements of pre-modern societies.

Keep up the great work!

I second Jayman’s comment

Interesting ideas. :) It’s also quite telling that the imperial capital ended up in another of the old imperial marches, the Ostarrîchi.

How different do you think the Dutch are from the Flemish? They’re their Dutch-speaking Catholic neighbours that have (from what I gather) never been part of the Dutch state. Flanders was a pretty successful area of Europe for a long time.

The Afrikaners of southern Africa don’t seem to be a very exceptional people considering their Dutch ancestry, though. I don’t know what happened with them.

Maybe off topic but it’s a shame the Dutch failed to defeat the Portuguese in trying to conquer Brazil and were then ultimately kicked out of the country. Reading what they had already done there it looks like they were on the path to creating something magnificent there, but now Brazil is quite unextraordinary having been colonised by the Portuguese. The world would have benefited greatly if Brazil went into Dutch hands rather than Portuguese hands :(

@Cyrus:

“The world would have benefited greatly if Brazil went into Dutch hands rather than Portuguese hands :(“

Like Indonesia?

i’d say urbanization might have some of the same effects as manorialization in terms of outbreeding but different pressures in other ways – maybe more dog eat dog, less cooperative?

Urbanization can’t be that much more dog eat dog. Remember the major differentiation is between working primarily with family members and working with out groups. Capitalism requires the ability to work with out groups. If the urban center becomes to anti-cooperative, it will cause a breakdown.

What the Urban center might help facilitate is the reliance not on Family to redress grievances due to broken contracts, but on a court system. A quick look into the Dutch and in particular the Frissians I found that they seem to have more of a republic make up. this is no doubt because they had a lower population density.

Consider if the population is small, then you can use a democracy, if it is larger, a republic, and if too large an oligarchy or Monarchy comes into play. These sizes are of course influenced by the relative tech and education of the population. Thus where as in classical antiquity democracy was barely able to be done in Athens, it was plausible in the Early US with a much larger population. The US population had greater literacy and the printing press made (miss)information distribution easier.

Getting back to the Dutch, those going out into these lands to drain and colonize them would have been risk takers by and large. This means that they would have probably been from the right hand side of most of the distribution curves. (IQ, risk taking, initiative, etc). These were not people going out to find a ‘garden of Eden’ ready to be plundered, but rather make new lands for themselves to farm, to work. – heck right there is the definition of the small business man.

Don’t forget that in 11-13th century we are seeing then highest temps of the Medieval warming period, Just before the start of the Little Ice Age (nominally 1306/07). I’m not sure what influence such warm temps might have on the population in context of this discussion, but they would have been there.

All the Belgians, including the Flemings, were briefly part of the Dutch state after the Napoleonic wars. They didn’t like it, and rebelled. That’s when Belgium was set up, and guaranteed by “The Powers”.

@Cyrus

What’s wrong with Afrikaners? They seem to have done very well for themselves.

[…] Timely as it is interesting, HBD Chick has a whopping: The Dutch, the Absence of Manorialism in Medieval Netherlands, and New York Values […]

“What’s wrong with Afrikaners?” You’ve not met any, then?

@JayMan – The Dutch didn’t settle in Indonesia in the way the Portuguese settled in Brazil or the British settled in the USA and Canada.

@AlexT – I don’t know, they just seem a bit backwards. For some reason they also lag behind the South Africans of British descent in income and education, which is strange because the Dutch are by all accounts smarter than the British.

@dearieme

I know a few. Met many more. Never noticed anything wrong with any of them.

@Cyrus and @Jayman, …. There is a LARGE difference between New Amsterdam and Brazil or Indonesia, mainly as Jayman and HBDChick like to point out – Gentics.

Most of what was New Amsterdam had at the time it became New York and is now an area filled with those of European decent, and largely at 1800 ‘core Europeans’. I will grant it isn’t 100% but without specific study, call it 75%+. The natives were gone, the non Europeans were imports from Africa mostly, and not a great part of the population, 25% might be to high. Today that ratio is probably below 50% core Europe – although with mixing, it is hard to tell exactly where the genes are without testing and knowing what genes are important.

Now in Brazil and Indonesia the reverse has happened. Mostly native born, non Europeans resided there, and today it is Mix or Native genes, not HBD’s core Europe ones.The same could be said of South Africa.

The only area – North of Rio Grande new world – that was colonized by core Europe and became a core Europe genetically dominated area. All others had European rulers for a time, but the population remained local, and has become mixed.

Something that just occurred to me – call it the genetics of the neighbors – is even if the groups don’t mix, the average skill set can prevent the core Europeans from advancing as much in the colony. Among other things, advancement is dependent on having the time to do just that. In antiquity, the ‘non farm labor’ was about 1% of population (or 99% were farmers). Since food is the first labor requirement, it makes a good starting point for figure what labor can be spared. In colonial America circa 1780 it was about 20% to 80% non farmers to farmers. Today it is less than 2% farmers. 98% of the people don’t have to farm. This frees them up for other labor, like school teacher, scientist, and blogger. So even if there had been as large of a Afrikaner population in South Africa as in Holland, they may not have been able to do as much because of lower economic output per capita.

Then the highly central and riverine/maritime nature of the Netherlands enabled the development of a highly commercialized (pre-Malthusian) economy, thus also resulting in especially strong selection for intelligence. (The modern Dutch are near the top according to PISA).

Fascinating stuff.

“the highly central and riverine/maritime nature of the Netherlands”: ‘central’ to what? It was so remote that the Romans scarcely penetrated there.

It became central when Europe’s economic center of gravity shifted north after the Dark Ages.

In particular, it was a central hub for the Rhennic trade route which connected Italy and the Med to the Hanseatic trade system – and which today has come to be called the “Blue Banana.”

The dutch were not influential as colonists. In Brazil they completely militarily defeated the portuguese in northern brazil and looked set to have an empire there. Then the first, enlightened, governor, (actually a german ) was recalled and the dominees arrived and attempted to impose calvinism. The local merchants revolted and threw the dutch out. No one was more surprised than portugal to get the northern coast back.

[…] Left Coast, Yankeedom, The Midlands, New France (Maine and Louisiana), New Netherlands (where we got the Roosevelts), Tidewater and the […]

You forgot one group in your original equasion: the vikings that became part of the population until about 1000. The counts of Holland descended form those, not unsimilar tot the Normans in Normandie etc. But unlike those Normans, they never left after theit arrival. (The city of Vlaardingen some years ago was proven to have some local decendants from peope a 1000 years before).