been meaning to do a follow up post on the bamileke of cameroon since … well, since last november! always on top of things here at the hbd chick blog. (*^_^*) so, at long last, here we go….

oh. in case you don’t recall or didn’t realize, i’ve been trying to track down other outbreeders around the world — populations which have avoided close relative marriage (closer than second cousins) over the long term (say 30 or 40+ generations) — to see what they’re like: what their family structures are like, what their social structures are like, if they’re corrupt or nepotistic or have a lot of infighting between families/clans, etc. i’m interested in finding out if there are any general behavioral traits common to outbreeders. same for the inbreeders, too, actually.

the bamileke are outbreeders. they avoid all marriage with anybody on their mother’s side of the family (their matrilineage), and also tend to avoid marriage to third cousins or closer on the father’s side [pg. 149]:

“The matrilineage is comprised of all the people descended through women from a common female ancestor. Since all female descendants of the matrilineage are considered his sisters, a man must not marry within this group. No specific taboos exist against marriage within a patrilineage, although most Bamileke who share a common male ancestor four generations back [i.e. a great-great-grandfather-h.chick] will not intermarry. Whereas members of a patrilineage live close to each other and regularly commune with each other, those of a matrilineage are not close and may, in fact, belong to different chiefdoms.”

the bamileke, however, like many african groups, practice polygamy which probably narrows the genetic relatedness in the population. i don’t have any figures on how much polygamy is practiced there.

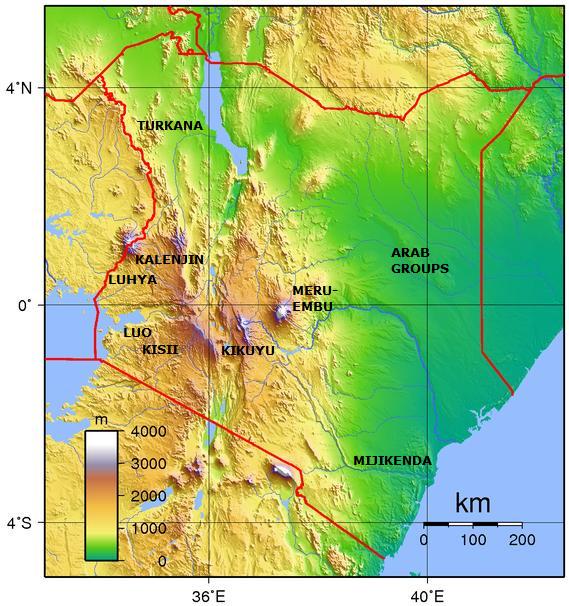

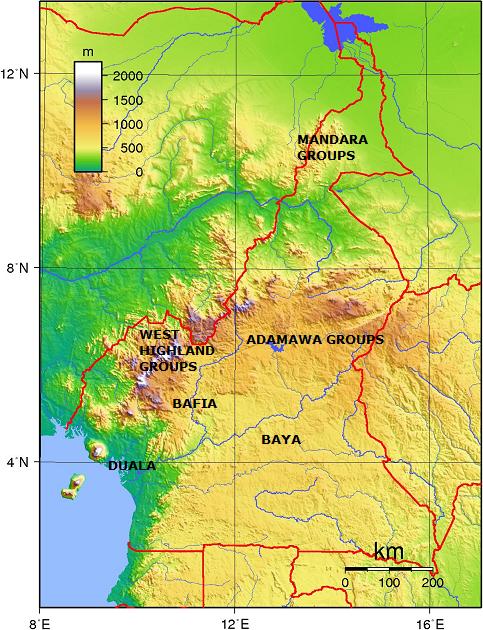

don’t know for how long the bamileke have been avoiding close cousin marriage, but i suspect that it is at least a few hundred years. the bamileke first came up here on the blog in a previous post, flatlanders vs. mountaineers revisited, in which we saw that they are some of the cameroon highlanders many of them living in very mountainous regions of cameroon, but yet their mating patterns — i.e. avoiding close cousin marriage — don’t seem to fit the broad pattern of highlanders or mountain folk typically inbreeding. apparently, however, the bamileke are fairly recent arrivals in the highlands, having migrated from the (flat) adamawa plateau somewhere around the 1600s [pg. 261 – links added by me]:

“As for the Bamileke, their ancient history is closely linked to that of the two previous groups. All came from the north, from the region today occupied by the Tikar. Their migration probably began in the seventeenth century and took place in successive waves.”

so, it could be that the bamileke are long-term outbreeders (because they originally came from a flatlander region) who transplanted themselves into more mountainous regions beginning ca. four hundred years ago. they don’t seem to have adopted a mountaineer economy — pastoralism for instance — but, rather, stuck to farming. what might have (ironically) saved them from eventually having to adopt pastoralism was the arrival of the germans who introduced coffee growing to the cameroon highlands. the bamileke quickly adopted the cash-crop system of coffee growing and trading with europeans. not sure about this, though — just a guess on my part.

it might be impossible to reconstruct the history of the bamileke people’s mating patterns from historical records (which will have been written almost solely by europeans, of course). if i find any published accounts by christian missionaries in cameroon, they might include some info on the bamileke. otherwise, genetic data (runs of homozygosity) would probably be the best way to discover how in- or outbred the bamileke are. for now, all i can say is that currently (in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries) the bamileke are outbreeders. and judging by their history, there’s a good chance that they’ve been outbreeders for a few hundred years, but that is just speculation on my part.

having said that, what are the bamileke like? what are their family types and social structures like?

traditional bamileke families do not appear to have been nuclear families, primarily because polygamy was (is) practiced, so that is unlike the outbred societies we’ve seen in western europe.

one subgroup of the bamileke, the bangwa (bangoua – in french), are described thusly [pg. 1]:

“Nor is Bangwa a ‘lineage-based’ society. Bangwa social life is not carried on in the all-embracing idiom of kinship, with personal loyalties and resources pooled in discrete unilineal descent groups. Kinship here is an individual business, with a person in the centre of a ramifying network of ties linking him with matrilineal and patrilineal kin, affines, creditor-lords, political superiors and so on. A Bangwa claims no clan or lineage membership, and no corporate group takes responsibility for any of his actions. Kinship is an aid to the business of making a living: tradiing, inheriting, acquiring a title, farming, ruling and marrying. And as the business of living is complex in Bangwa so is the kinship system.”

these features — not having tight clans or even lineages, individuals having to take responsibility for their own actions — are very much like what we see in the long-term outbreeding european populations. don’t know if the rest of the bamileke are like the bangwa in these regards, but i’m guessing yes, since i haven’t read any descriptions anywhere of bamileke peoples engaging in blood feuds or having a wergeld-like system. this absence of tight clans/kindreds seems outbred to me.

however [pg. 351]:

“Customary political structures revolve around kinship, which the Bamileke define by dual descent — patrilineal ties typically determine village residence and rights to land, but matrilineal ties define ritual obligations and the inheritance of movable property.”

so larger kinship groupings are not totally unimportant to the bamileke.

from the previous post (and from this article [pdf]):

“Although the group solidarity of the Bamileke is strong, individual achievement is highly valued. Members of the group are expected to exercise individual initiative in the pursuit of economic goals. Individual acquisition of economic resources including private property, money, and other remuneration is stressed. Other cultural characteristics of the group that have been invaluable to their entrepreneurial skills are discussed below….

“[T]he social status of an individual in this ethnic group is not rigidly fixed; individuals — male or female — can improve their condition in life and are expected to do so. Commercial and business success is one of the most highly valued routes to prestige and status. Bamileke women are also expected to achieve economic and comnercial success and there are few traditional limits placed on their economic participation….

“The traditional values of the Bamileke stress individual competition and overt displays of ‘getting ahead’. Individual Bamileke are expected to compete and to surpass each other’s accomplishments. The emphasis on competition is not limited to economic activities, but is a feature of personal relationships as well: within families, children are expected to compete with their siblings; sons and daughters are encouraged to surpass the achievements of their parents….

“[P]oorer relatives are not expected or allowed to lay claim to or live off the riches of wealthier family members….

“A final feature of traditional society which must be noted is the system of succession and inheritance. Of all the elements characteristic of Bamileke social organization, this feature has been fundamental and has had far-reaching implications for the rate and pace of Bamileke participation in economic growth, development, and change. Succession and inheritance rules are determined by the principle of patrilineal descent. According to custom, the eldest son is the probable heir, but a father may choose any one of his sons to succeed him. An heir takes his dead father’s name and inherits any titles held by the latter, including the right to membership in any societies to which he belonged…. The rights in land held by the deceased were conferred upon the heir subject to the approval of the chief, and, in the event of financial inheritance, the heir was not obliged to share this with other family members. The ramifications of this are significant. First, dispossessed family members were not automatically entitled to live off the wealth of the heir. Siblings who did not share in the inheritance were, therefore, strongly encouraged to make it on their own through individual initiative and by assuming responsibility for earning their livelihood….

“A notable feature of the group is the complementarity between individualism and collective unity. Individuals are expected to make their own way in the world while retaining a strong ethnic identity and group association. This interact is one of the factors accounting for their economic success. Each individual, for example, is expected to contribute as much to the group as he receives in return. Thus, cooperation is essential. The group is perceived of as an interdependent system based on the strength of individual links….

“A principal Bamileke belief is that individuals are, in the final analysis, responsible for their own fate. One makes one’s way in society on the basis of individual qualities. Status distinctions and rank are not rigidly fixed and there is always the possibility of advancement.”

so here we have: individualism, extended family NOT being able to automatically rely on other members of the extended family, no precise inheritance rules (which is something emmanuel todd identifies as a trait of absolute nuclear family societies), and the collective unity of the larger group (NOT any family group). these are all traits that are found in outbred, “core” europe — although they are expressed somewhat differently in northwest europe vs. cameroon.

the bamileke also have a lot of voluntary associations, another characteristic common in outbred europe and not normally found in inbred populations — at least none of the inbred populations i’ve looked at so far [pg. 42]:

“The original function of these societies was to administer initiation rites, but in societies with a more complex economy and polity, both male and female associations grew in importance by assuming a plurality of administrative and commercial functions as well, such as tax collection, price control in markets, maintenance of public order, and organization of collective work. The *mandjon* societies of Bamileke men and women provide good examples of such traditional associations. The women’s *mandjon* are presided over by the mother of the *fon* or chief — there are over a hundred such chiefdoms in Bamileke territory — and its members help each other in agricultural work. The *mandjon* used to meet on a weekly basis to organize such work. In addition to associations that fit into the political structure of Bamileke society, there are also many autonomous associations based on neighborhood. Aside from ritual functions (such as divination and faith healing) they also act as savings groups and associations for mutual assistance. More recently, Bamileke associations…have been adapted to the needs of urban living and have led to a proliferation of voluntary membership clubs that provide mutual aid, companionship for immigrants, and entertainment. The savings groups are maintained by members paying in fixed amounts at weekly meetings, taking turns in receiving the entire sum. Membership is not restricted to a single saving association and the Bamileke tend to join them as soon as they earn money.”

interestingly, the bamileke are probably the most successful group in cameroon economically speaking — and they are also strongly nationalistic [pg. 65]:

“In the towns and cities, they are known for their skills at running small and large businesses and for their professional abilities…. During the years of the French colonial empire, the Bamileke were leaders in the nationalistic rebellion, especially the 1955 uprising that led to Cameroon’s independence. Today the Bamileke are extremely influential in the Cameroonian commercial economy. They are also one of the major constituencies of the Union de Populations du Cameroun (UPC), the fiercly nationalistic political party.”

i haven’t found out anything yet on corruption in bamileke society — although there seems to be plenty of it in cameroon. can’t imagine that they’re very nepotistic since the members of extended families are not obliged to help one another out — nor is aid to be expected — but you never know. i will endeavor to find out more!

(^_^)

previously: guess the population! and the semai

(note: comments do not require an email. bamileke elephant masks!)