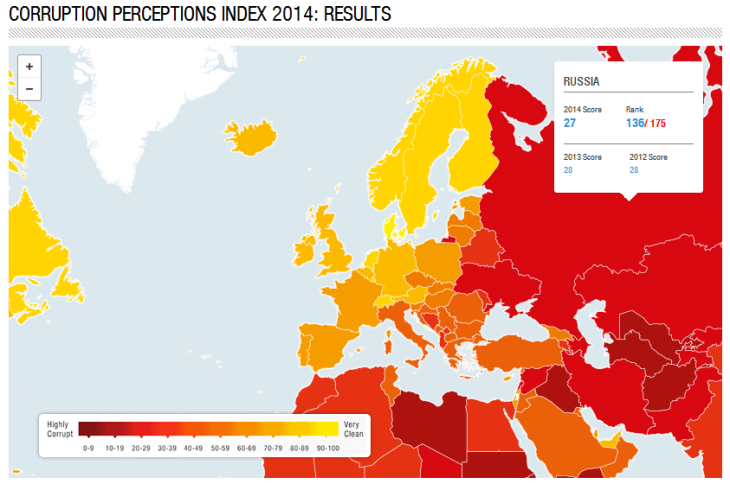

it is a truth universally acknowledged, that whenever someone posts a map like this…

…on twitter, that a chorus of people will respond: oh, just look at the terrible effects communism had on eastern europe! for no good reason really because, as we all know, correlation does not equal causation — although it does “waggle its eyebrows suggestively and gesture furtively while mouthing ‘look over there.'”

just because soviet regimes were present in the past in the same areas of europe where there are high corruption levels today does not mean the one is the cause of the other. (and anyway…look at the regions beyond europe! or southern europe, for that matter.) the relationship is certainly suspicious though, and it wouldn’t be surprising if the two were somehow connected.

one way to try to settle this debate would be to look at pre-soviet corruption rates in eastern europe versus the west to see if the situation was any different beforehand.

i have not done that in this post, in large part because i don’t speak any slavic or other eastern european languages, but primarily because it seemed like way too much work. instead, i’m going to take a look a civicness, a set of behaviors — along with things like intelligence, low amounts of corruption, and low levels of violence — that many researchers reckon are necessary in order to have western-style liberal democracies and economies, if that’s what you want in life. i’ll be focusing on russia, again just to kept this little project manageable. but first, italy.

_____

in Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy, robert putnam (yes, that robert putnam) concluded that democracy in northern italy functions better than in the south because the north has had a longer tradition — stretching back to the middle ages — of civicness or of having a civic community. (see previous post: democracy in italy.) according to putnam [pgs. 88-89, 91]:

“Citizenship in the civic community entails equal rights and obligations for all. Such a community is bound together by horizontal relations of reciprocity and cooperation, not by vertical relations of authority and dependency. Citizens interact as equals, not as patrons and clients nor as governors and petitioners….

“Citizens in a civic community, on most accounts, are more than merely active, public-spirited, and equal. Virtuous citizens are helpful, respectful, and trustful towards one another, even when they differ on matters of substance….

“One key indicator of civic sociability must be the vibrancy of associational life.”

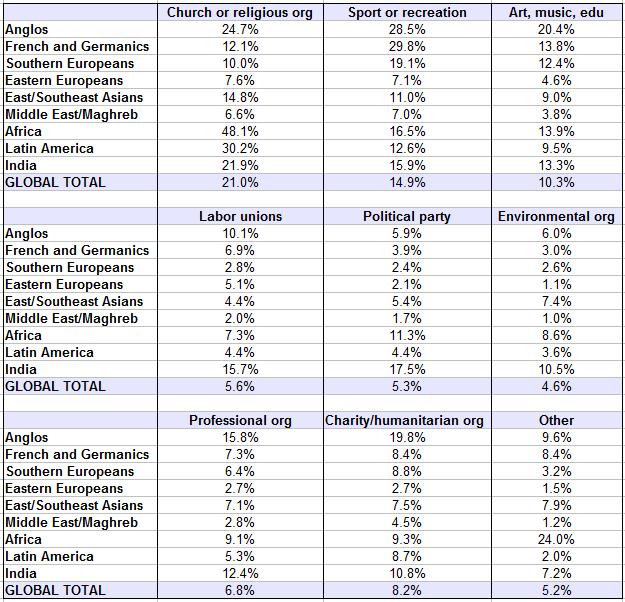

in civic societies and civic societies ii, i looked at (self-reported) participation rates in voluntary associations across the world as found in the 2005-2008 wave of the world values survey. specifically, i tallied up the number of individuals who responded that, yes, they were ACTIVE members of the following voluntary associations (thus giving some indication of how civic-minded each of the populations is):

– Church or religious organization

– Sport or recreation organization

– Art, music or educational organization

– Labour union

– Political party

– Environmental organization

– Professional association

– Charitable organization

– Any other voluntary organization

the response rates for eastern europe were abysmal, often vying for last place with the middle east (see previous post for more):

not much has changed in the latest wave (2010-2014). here, for example, are the active membership rates for the russian federation for each of the organization types — the first figure is from the 2005-2008 wave, the second from 2010-2014:

– Church or religious organization = 2.60% – 2.00%

– Sport or recreation organization = 5.90% – 2.40%

– Art, music or educational organization = 4.20% – 1.50%

– Labour union = 3.40% – 2.00%

– Political party = 0.80% – 0.50%

– Environmental organization = 0.40% – 0.40%

– Professional association = 1.60% – 1.40%

– Charitable organization = 1.10% – 0.6%

– Any other voluntary organization = n/a – 1.4%

as joseph bradley says in Voluntary Associations in Tsarist Russia: Science, Patriotism, and Civil Society (2009), russia is “not known as a nation of joiners.” apparently not! (mind you, i am not in a position to cast any stones on this account. *ahem*)

_____

but were the russians more civic-minded before the revolution?

unfortunately, i don’t have any figures which can be directly compared to our modern world values surveys, but, yes, there was some amount of participation in voluntary civic institutions in russia in the two hundred years or so preceding 1917. however, civic participation didn’t begin in russia until the mid-1700s (and that is a key point to which i’ll return), and for most of that period, it occurred mostly among the upper classes. participation rates did grow across the nation and classes over the next century and a half, until just after the revolution of 1905 when there was a rapid rise in one sort of voluntary association — consumer cooperatives — among all classes of russians. however, civil society was still comparatively shallow in early-twentieth century russia — it hadn’t fully penetrated the whole of society by that point yet because the concept was so relatively new to the populace. here is laura engelstein in “The Dream of Civil Society in Tsarist Russia: Law, State, and Religion” (2000) quoting the sardinian antonio gramsci on the matter [pg. 23]:

“On the margins of the European state system, sharing but not fully integrating the Western cultural heritage, Russia, it is said, has always lacked just these civic and political traits. Antonio Gramsci provides the classic statement of this contrast: ‘In Russia,’ he wrote in the 1920s, ‘the state was everything, civil society was primordial and gelatinous; in the West there was a proper relation between state and civil society, and when the state trembled a sturdy structure of civil society was at once revealed.’ When in 1917 the Russian autocracy not only trembled but tumbled to the ground, there was no ‘powerful system of fortresses and earthworks,’ in Gramsci’s phrase, to prevent the Bolsheviks from erecting another absolutist regime in its place.”

civic society in russia first came to life under catherine the great (1729-1796), who did go some way to promote enlightenment ideals in the empire; perhaps more so when it came to the arts rather than politics, but still…it was a start, albeit one restricted in extent. from engelstein again [pg. 26 – my emphasis]:

“Eighteenth-century Russia had a lively public life. Private presses, a market in print, debating societies, literary salons, private theaters, public lectures, Masonic lodges — all linked inhabitants of the capitals and provincial centers in something of an empirewide conversation. Yet this world was limited in scope, audience, and resources and was fatally dependent on the autocrat’s good will. Catherine, when it pleased her, cracked down on independent publishers.”

this public life did continue to grow, however, although in fits and starts. nicholas i (1796-1855) was not too thrilled by it all, and alexander i (1777-1825) actually banned the freemasons, but by the nineteenth century, alexander ii (1818-1881) was, for a tsar, positively a radical when it came to permitting and promoting civic society as was evident in his great reforms. by the late nineteenth century then [pg. 16]:

“…an increasingly active public sphere of debate that included advocacy and representation was no longer in doubt in tsarist Russia. Thus well before the Revolution of 1905, the groundwork was laid for the participation of private associations in the public arena.”

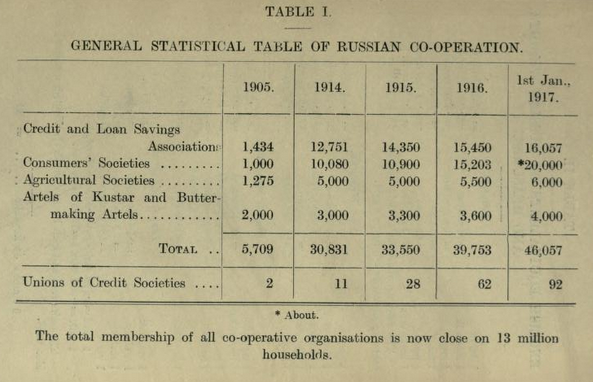

the practice of joining voluntary organizations came later to the russian lower classes. consumer cooperatives began to appear in russia and the empire in the 1860s, but these first cooperatives were organized and run by the upper classes. peasants and workers would’ve been customers only. cooperatives among middle class professionals in towns and cities appear in the early-1890s. the idea spread to villages in 1900 via proselytizing intellectuals (also worth noting), and after 1905, the cooperative movement exploded right across the country. from The Co-operative Movement in Russia: Its History, Signficance, and Character (1917) by j.b. bubnoff — delightfully published in manchester by the co-operative printing society limited (so the work could be a bit biased) [pg. 49]:

“In 1891 consumers’ societies were formed in towns among the lower-grade officials, various classes of employees, teachers, members of liberal professions, and other sections of the population. These societies were of two types. One open only to members of a particular class of officials or to employees of a particular firm or institution; the other was open to all. These latter societies were already marked by the spirit of independence.

“Throughout this period the number of consumers’ societies was not large, and their output was small…. In 1900 the position was the same. Beginning from 1900, the Co-operative Movement spread in the villages…. [T]he first consumers’ societies in the villages were initiated by the intellectuals and by the authorities and were not the outcome of free enterprise on the part of the peasants themselves. At the end of the last century, and particularly at the beginning of the present one, an agrarian movement spread among the peasantry and ended in the revolution of 1905.”

by 1917, provided bubnoff wasn’t exaggerating, there were ca. 20,000 consumer cooperatives in russia (bubnoff notes that the other organizations listed in the table below — credit and loan savings associations, agricultural societies, and the artels — were all either government run or arranged by the large landowners, so they weren’t really voluntary associations in the sense of being organized by the members.):

again, though, this is late for finally getting around to launching civic institutions in your country. nineteen hundred and seventeen (1917) is very, very late compared to what happened in northwestern europe. even compared to what happened in northern italy. as valerie bunce says in “The Historical Origins of the East-West Divide: Civil Society, Politcal Society, and Democracy in Europe” [pg. 222]:

“By the end of the nineteenth century, then, it was evident that there were two Europes, long separated by their histories and, thus, by their politics, economics, social structure, and culture.”

not to mention their evolutionary histories.

_____

so how did northwestern “core” europe (including northern italy) differ from russia historically as far as participation in civic institutions goes? the short answer is: civicness in “core” europe began centuries before it did in russia or the rest of eastern europe, at least 500-600, if not 800-900, years earlier.

here is putnam on the formation and functioning of communes in northern italy beginning in the 1000s [pg. 124-126]:

“[I]n the towns of northern and central Italy…an unprecedented form of self-government was emerging….

“Like the autocratic regime of Frederick II, the new republican regime was a response to the violence and anarchy endemic in medieval Europe, for savage vendettas among aristocratic clans had laid waste to the towns and countryside in the North as in the South. The solution invented in the North, however, was quite different, relying less on vertical hierarchy and more on horizontal collaboration. The communes sprang originally from voluntary associations, formed when groups of neighbors swore personal oaths to render one another mutual assistance, to provide for common defense and economic cooperation…. By the twelfth century communes had been established in Florence, Venice, Bologna, Genoa, Milan, and virtually all the other major towns of northern and central Italy, rooted historically in these primordial social contracts.

“The emerging communes were not democratic in our modern sense, for only a minority of the population were full members…. However, the extent of popular participation in government affairs was extraordinary by any standard: Daniel Waley describes the communes as ‘the paradise of the committee-man’ and reports that Siena, a town with roughly 5000 adult males, had 860 part-time city posts, while in larger towns the city council might have several thousand members, many of them active participants in the deliberations….

“As communal life progressed, guilds were formed by craftsmen and tradesmen to provide self-help and mutual assistance, for social as well as for strictly occupational purposes. ‘The oldest guild-statute is that of Verona, dating from 1303, but evidently copied from some much older statute. “Fraternal assistance in necessity of whatever kind,” “hospitality towards strangers, when passing through the town”…and “obligation of offering comfort in the case of debility” are among the obligations of the members.’ ‘Violation of statutes was met by boycott and social ostracism….’

“Beyond the guilds, local organizations, such as *vicinanze* (neighborhood associations), the *populus* (parish organizations that administered the goods of the local church and elected its priest), confraternities (religious societies for mutual assistance), politico-religious parties bound together by solemn oath-takings, and *consorterie* (‘tower societies’) formed to provide mutual security, were dominant in local affairs.”

in general, nothing like this existed in medieval russia (or eastern europe) — not on this scale anyway — the novgorod republic, which lasted for three centuries and came to an end in 1478, probably being the most notable exception. eastern european society was still very much founded upon the extended family for much of the period (although, again, in certain times and locales that was not the case — russia’s a big place). only a handful of merchants’ guilds were given permission to exist in russia between the fourteenth and eighteenth centuries, and the powers that be (including the orthodox church) regularly suppressed craftsmen’s guilds [pg. 13]. by contrast, northern italy was full of civic-mindedness already by the high middle ages.

meanwhile, in england (and other parts of northwestern europe) [pgs. 3-4]:

“As a form of voluntary association, bound by oath and by a (usually modest) material subscription, the fraternity or guild was widespread in late-medieval England and continental Europe. Both the ubiquity and the frequency of the form have been underlined by recent historical case-studies. While the particular purpose and activities of a fraternity might be infinitely various, the organization may be characterized in general as combining pious with social, economic, and political purposes. Its declared aims invariably included important religious functions, expressed in the invocation of a saintly patron and an annual mass with prayers for deceased members. With equal certainty, the annual feast day would bring the members together for a drink or a meal to celebrate their community. The overwhelming majority of English guilds admitted women alongside men: a feature generally characteristic of guilds of medieval northern Europe, although not so prevalent in the Mediterranean world. Sometimes described in modern English accounts as ‘parish fraternities’, these clubs indeed were often founded by groups of parishioners and regularly made use of an altar in a parish church as a devotional focus; yet they as often drew their memberships from a wider field than that of the parish, whose bounds they readily transcended…. An individual might join more than one guild, thereby extending still futher the range of his or her contacts. A significant minority of fraternities crystallized around a particular trade…. The overwhelming majority of guilds, however, were not tied by such association to a single craft, but brought together representatives of various trades and professions.”

extraordinarily, one type of fraternity — of non-kin remember (the whole point of voluntary associations is that they’re made up of non-kin) — appeared in england as early as the late-800s. from a previous post, the importance of the kindred in anglo-saxon society:

“the *gegildan* appears in some of the anglo-saxon laws in the late-800s as an alternative group of people to whom wergeld might be paid if the wronged individual had no kin. by the 900s, though, in southern england, the gegildan might be the only group that received wergeld, bypassing kin altogether. from Wage Labor and Guilds in Medieval Europe [pgs. 39-42]:

“‘The laws of King Alfred of Wessex, dated to 892-893 or a few years earlier, are more informative about the *gegildan*. Again, the context is murder and the wergild — the compensation required for the crime. By Alfred’s time, if not during Ine’s, the *gegildan* is clearly a group of associates who were not related by blood. The clearest example of this is in chapter 31 of the laws: ‘If a man in this position is slain — if he has no relatives (maternal or paternal) — half the wergild shall be paid to the king, and half to the *gegildan*.’ No information exists on the purpose of the *gegildan* other than its role as a substitute for kinship ties for those without any relatives. These associates, who presumably were bound together by an oath for mutual protection, if only to identify who was responsible, would benefit anyone, whether the person had relatives or not…. Although the evidence from the laws of Ine may be read either way, the *gegildan* seems to be an old social institution. As seen more clearly in the tenth and eleventh centuries, it acquired additional functions — a policing role and a religious character.

“‘The nobles, clergy, and commoners of London agreed upon a series of regulations for the city, with the encouragement and approval of King Athelstan, who caused the rules to be set down some time in the late 920s or 930s. The primary purpose of these ordinances was to maintain peace and security in the city, and all those supporting these goals had solemnly pledged themselves to this *gegildan*. This type of inclusive guild, sometimes referred to as a peace guild, was an attempt to create one more additional level of social responsibility to support the king and his officials in keeping the peaces. This social group of every responsible person in London is a broad one, and the law does not use the term *gegildan* to describe the association in general….

“‘The idea of a guild to keep the peace was not limited to London, and a document from the late tenth century contains the rules and duties of the thegn‘s guild in Cambridge. This guild appears to have been a private association, and no king or noble is mentioned as assenting to or encouraging this group. Most of the rules concern the principle purposes of this guild — the security of the members, which receives the most attention, and the spiritual benefits of membership itself. The guild performed the tasks of the old *gegildan*: the members were obliged to defend one another, collect the wergild, and take up vengeance against anyone refusing to pay compensation. The members also swore an oath of loyalty to each other, promising to bring the body of a deceased member to a chosen burial site and supply half the food for the funeral feast. For the first time, another category of help was made explicit — the guild bound itself to common almsgiving for departed members — and the oath of loyalty the members swore included both religious and secular affairs. Although in many respects this guild resembles a confraternity along the lines Hincmar established for the archdiocese of Rheims, the older purpose of the group — mutual protection with its necessary threat of vengeance — makes the Anglo-Saxon guild something more than a prayer meeting. To include almsgiving to members in distress would be a small step, given the scope of activities this guild established. There is no sign that the thegns cooperated in any economic endeavors, but older rules of rural society had already determined methods of sharing responsibility in the villages, and the thegns cooperated on everything that was important in their lives. The thegns of Cambridge had a guild that resembles in some important ways the communal oath, that will be discussed below, of some Italian cities in the next century.'”

the gegildan of early medieval england, then — a voluntary association, a fraternity — appeared on the scene something like two hundred years before the communes of northern italy arose, three hundred plus years before the novgorod republic was formed, and nearly nine hundred years before the russians gave civiness another shot (after novgorod). i’m not aware of any earlier such associations in western medieval europe, although they may have existed. it appears, too, that the gegildan appeared in situ in england, a newly developed social structure to take over some of the earlier functions of the rapidly disappearing kindred (including feuding and protection), although maybe the concept was imported from the carolingians — the heart of the preceding frankish kingdoms, austrasia, was where manorialism had begun, which was then imported across the channel, so perhaps the gegildan concept was as well.

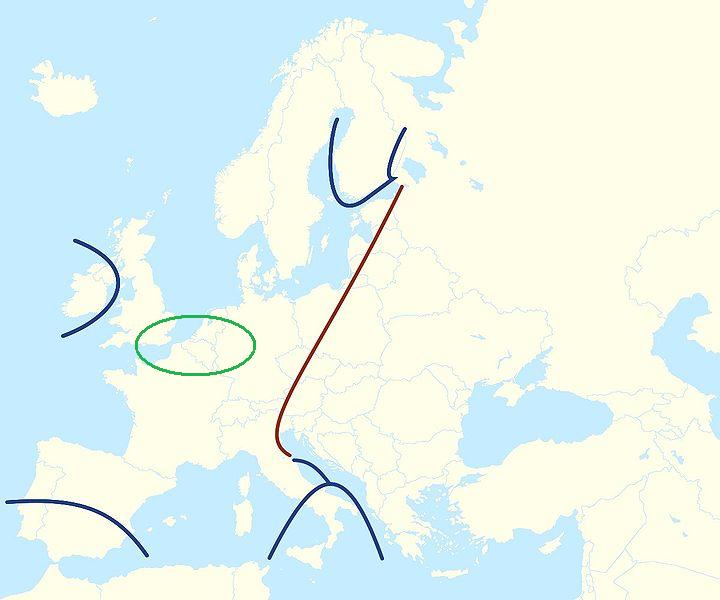

whatever the case, it’s in the core of “core” europe, once again, that we find the earliest evidence for behavioral patterns that are now the hallmarks of western civilization: late marriage and nuclear families, lowest levels of cousin marriage for the longest period of time, low levels of violence, high levels of civic-mindedness (see above), universalism, unparalleled accomplishment — they all appear earliest (in medieval europe), and are still the strongest, in this central area (very roughly the area indicated by the green oval on this map).

so, now we come to it: why? why was it “evident” by the end of the nineteenth century that there were two europes, and what do all these long-standing historical differences have to do with it?

_____

the ultimate cause must lie in our biologies. humans are biological creatures, so there’s no way around it. we know that all behavioral traits are heritable, so we have to look to differences in the populations’ genetics and evolutionary histories.

as i wrote recently: evolution in humans is ongoing, recent, can be pretty rapid (within some constraints), and has been/is localized (as well as global). in fact, human evolution has sped up since the agricultural revolution since the number of individuals, and therefore mutations, on which natural selection might work skyrocketed in post-agricultural societies. remember, too, that “every society selects for something,” and that we’re talking about frequencies of genes in populations and that those frequencies can fluctuate up and down over time.

so there is NO reason NOT to suppose that the differences in behavioral traits that we see between european sub-populations today — including those between western and eastern europe — aren’t genetic and the result of differing evolutionary histories or pathways.

even rapid evolution takes time, though. we’re not talking one or two generations, but more like thirty or forty — fifty’s even better. point is, evolutionary changes don’t only occur on the scale of eons. they can also happen over the course of centuries (again, multiples of centuries, not just one or two). the circa eleven to twelve hundred years since the major restructuring of society that occurred in “core” europe in the early medieval period — i.e. the beginnings of manorialism, the start of consistent and sustained outbreeding (i.e. the avoidance of close cousin marriage), and the appearance of voluntary associations — is ample time for northwestern europeans to have gone down a unique evolutionary pathway and to acquire behavioral traits quite different from those of other europeans — including eastern europeans — who did not go down the same pathway (but who would’ve gone down their own evolutionary pathways, btw).

what i think happened was that the newly created socioeconomic structures and cultural (in this case largely religious) practices of the early medieval period in northwest “core” europe introduced a whole new set of selective pressures on northwest europeans compared to those which had existed previously. rather than a suite of traits connected to familial or nepostic altruism (or clannishness) being selected for, the new society selected for traits more connected to reciprocal altruism.

before the early medieval period, northwest europeans — looking away from the urbanized gallo-romans who may have been something of a special case (more on them another day) — had been kin-based populations of agri-pastoralists whose societies were characterized by inter-clan feuding, honor/shame (vs. integrity/guilt), and particularism (vs. universalism). i think these traits were under constant selection in those populations because: reproductive success in those societies was dependent upon one’s connection to, and one’s standing within, the extended kin-group, so, thanks to being tied to kin rather than non-kin, nepotistic altruism genes would’ve been favored over reciprocal altruism ones; the extended kin-group was the element within which most individuals would’ve interacted with others, those others being related individuals who would’ve been likely to share the same nepotistic altruism genes (alleles) [see here for more]; and cousin marriage was rife, which again would’ve further fuelled the selection for these genes, since members of the same kin-group would’ve had an even greater likelihood of sharing the same versions of their nepotistic altruism genes.

pretty much the opposite happened during the early and high middle ages in “core” europe. manorialism pushed for nuclear families rather than extended family groupings, and so people began to interact more with non-kin rather than kin, enabling the selection for more traits related to reciprocal altruism. the avoidance of close cousin marriage meant that family members would’ve shared fewer altruism genes in common, so any selection for nepotistic altruism would’ve slowed down. and once voluntary associations of non-kin appeared, the selection for reciprocal altruism really would’ve (or, at least, could’ve) taken off. reproductive success was no longer dependent upon connections to the extended family group, but, rather, unrelated individuals living with the community.

the manor system developed in the 500s in “core” europe (austrasia), but did not arrive in russia (and much of eastern europe) until the late medieval/early modern period. (it never got to the balkans.) the extended family was most likely gone on the manors in the west by the 800s (see mitterauer), although it is conceivable that the nuclear families found on the manors in the earliest days were residential nuclear familes rather than the fully atomized ones that we see in the west today. certainly by the 1500s, there are no longer any traces of the extended family among “core” europeans (although there are still some pockets). the avoidance of cousin marriage was underway in earnest by the 800s (possibly earlier, but definitely by the 800s). it was still on shaky ground as late as the 1400s in russia. and, as we’ve seen, voluntary associations appeared very early in “core” western europe, but only very recently in russia (and, presumably, other areas of eastern europe).

_____

most of you will recognize this as the hajnal line story (yet again!) with a few new nuances thrown in. manorialism, outbreeding, and voluntary associations all began in “core” europe — again very roughly the area outlined by the green oval on the map below (the other lines indicate, again roughly the extent of the hajnal line) — and they spread outwards from there over time, eventually reaching russia and other parts of eastern europe, but not until very late. (and the manor system in russia, once it was adopted there, was of a very different form than what had existed in western europe.)

inside the hajnal line, which (imo) reflects the extent of the strongest selection for behavioral traits related to reciprocal altruism over nepotistic altruism, the populations have stronger democratic traditions, are more civic-minded, are less corrupt, and score higher on individualism (vs. collectivism) on hofstede’s idv dimension than the populations outside the hajnal line. (please, see my big summary post on the hajnal line for more details.) all of these behavioral patterns “fit” better with the idea that these populations are characterized by innate reciprocal altruism tendencies rather than more nepotistic altruism ones. the populations outside the hajnal line seem to be more oppositely inclined.

there is no doubt that soviet communism wreaked havoc on eastern european populations. some untold millions died in the gulags, families and towns and villages were ripped apart, political repression was beyond belief. but smart money says that, along with civicness, many of the “non-western” features of contemporary eastern europe — high corruption rates, etc. — have deeper roots, and are not the consequences of communism, but rather of recent evolution by natural selection.

previously: civic societies and civic societies ii and democracy in italy and big summary post on the hajnal line

(note: comments do not require an email. sorry there’s no tl;dr summary!)