when it comes to clan-based societies vs. nation-states and all that, the reigning paradigm is that peoples resort to relying on their extended families/clans/tribes for all sorts of things like justice and economic support in the absence of a (strong?) state, but if they somehow miraculously acquire a state, people quickly drop the connections with their extended families. this to me seems completely upside-down-and-backwards.

never mind, for instance, that there have been strong states in the middle east since…*ahem*…the days of hammurabi if not before, and yet for some reason middle easterners are amongst the most clannish peoples on the planet (see: syria) — and i mean clannish as in actually relying on their clans in their daily lives. and never mind that the chinese — especially the southern chinese — still organize themselves along clan lines, too, with their clan clubhouses and everything — even though they’ve had really strong and powerful states for millennia as well.

see? upside-down-and-backwards.

what appears to be the case, rather, is that, for whatever (*cough*genetic*cough*) reasons, people stop relying on their extended families/clans when they stop being very closely related to those family members, i.e. after a long period of outbreeding (avoiding cousin or other forms of close marriage). i’ve already shown in a previous post that the importance of the clan/kindred in anglo-saxon england was waning in the early 900s (in southern england anyway), before england was unified, so before there was a nice, cozy state for people to fall back on. the same appears to be true of the medieval french (at least some of them — there are regional differences, as there are in britain).

but i’m getting ahead of myself. first things first: picking up where we left off at the end of the last post on medieval france — mating patterns of the medieval franks. let’s look at the importance of the kindred and feuding amongst the franks. then i’ll get to how and when the franks/french dropped all the kindred and feuding business.

for those of you who don’t want to wade through all the details, tl;dr summary at the bottom of the post (click here). you’re welcome! (^_^)

_____

as we saw in the previous post, the franks — and really i mean the salian franks who gave rise to the merovingian dynasty in austrasia — like all the other pre-christian germanic groups (and the pre-christian irish and britons and scots, too) married their cousins. who knows how much, but enough that the various christian missionaries to these groups raised loud and very vocal objections to their marriage practices.

the result, imho, is that frankish society — like early medieval anglo-saxon society — was “clan”- or kindred-based. from The Laws of the Salian Franks (1991) [pgs. 39-41]:

“The Frankish family was the small family usually found among the other Germanic barbarians: it consisted of husband, wife, minor sons, unmarried daughters, and other dependents including half-free dependents (*lidi*) and slaves. However, although the basic family group was the same for the Franks as for most other Germanic barbarians who settled within the territory of the Roman Empire, the Franks relied more heavily on the larger kin group than did the Burgundians, Visigoths, or Lombards (it is difficult to know about the Anglo-Saxons, for the early Anglo-Saxon laws are uninformative on this subject)….“

that last bit is debatable, but anyway…

“The kin group was important because the individual alone, or even with his immediate family, was in a precarious position in Frankish society. One needed the support of a wider kin to help him bring offenders against his peace before the courts, and one needed kin to help provide the oathhelpers that a man might be required to present in order to make his case or to establish his own innocence before the court. These roles of the kin are familiar to all the Germans. But the Frankish kin group had further responsibilities and privileges. For example, if a man were killed, his own children collected only half of the composition due, the remaining half being equally divided between those members of his kin group who came from his father’s side and those who came from his mother’s side (LXII, i)….

“The right of the kin group to share in the receipt of composition involved also the responsibility for helping members of the group to pay composition. If a man by himself did not have sufficient property to pay the entire composition assessed against him, he could seek help from his closest kin, father and mother first, then brothers and sisters. If sufficient help was still not forthcoming, more distant members of the maternal and paternal kin (up to the sixth degree, i.e., second cousins [XLIV, 11-12]), could be asked to help. This responsibility of the kin to aid their kinsmen is known in Frankish law as *chrenecruda* (LVIII)….

“The importance of the kin group should thus be obvious, and added importance derived from the fact that one shared in the inheritance of one’s kin up to the sixth degree should closer heirs be lacking. Normally the advantages and disadvantages of belonging to a kin groups (legally related in an association known as parentela) evened themselves out, and the security of association plus the opportunity to inherit well justified the potential liability of the kin. However, on occasion the liabilities overshadowed the advantages. The debts of an uncontrollable relative might endanger a man’s property, or movement away from the area in which the kin group lived might have made the operation of parentela awkward if not impossible. So the law provided the means whereby a man could remove himself from his kin’s parentela, thereby avoiding responsibility for his kin — but in return he forfeited his position in the line of inheritance of that kin group (LX).”

and then there was the feuding as well. from Language and History in the Early Germanic World (2000) [pgs. 50-51]:

“The other form of protection provided by the kindred concerns blood-vengeance and the prosecution of a feud, for these act as a disincentive to violence and therefore offer protection in advance. It is not enough to define a feud as a state of hostility between kindreds; we must extend it to the threat of such hostility, but also, if the mere threat fails to prevent the outbreak of actual hostility, to a settlement on terms acceptable to both parties by means of an established procedure. In other words, the feud is a means of settling disputes between kindreds through violence or negotiation or both….

“Central to feuding is the idea of vengeance, the willingness of all members of a kindred to defend one of their number and to obtain redress for him…. If a conflict nonetheless broke out it was waged not between individuals, but collectively between kindreds, as is best revealed by the way in which satisfaction could be obtained by vengeance on any member of the culprit’s kindred, not necessarily on the perpetrator himself. An offence to one was therefore an offence to all, as is most pithily expressed by Gregory of Tours in the case of a feud involving a woman with the words: *ad ulciscendam humilitatem generis sui*. In this case the kindred exacts vengeance from one of its members who is felt to have disgraced it; a refusal to act thus would have brought even greater shame up the kindred. An example like this shows, even in the language used, just what difficulties the Church had to face in dealing with such a mentality, for the word *humilitas*, in Germanic eyes the ‘humiliation’ or ‘shame’ done to the kindred, was for the Christian the virtue of humility. This virtue, including even a readiness to forgive an insult, was the undoing of Sigbert of Essex who, so Bede reports, was killed by his kinsmen who complained that he had been too ready to forgive his enemies and had thereby brought dishonour on his kindred. Such forgiveness and willingness to abandon the duty of feuding dealt a shocking blow to the kindred as a central support of Germanic society.”

the gauls also practiced feuding, so their society was probably clan- or kindred-based, too. from Medieval French Literature and Law (1977) [pg. 67]:

“[The vendetta’s] sole justification was a prior injury or offense. Sanctioned in Roman Gaul in cases of murder, rape, adultery, or theft, the blood vengeance implied a solidarity of family lineage….”

_____

today the french are (mostly) not a clannish, feuding, kindred-based society — especially compared to, say, the arabs. what happened? when did they quit being clannish?

the kindred-based blood feud was still common during the carolingian empire (800-888) despite efforts of the authorities (the state!) to put a stop to it. from The Carolingian Empire (1978, orig. pub. 1957) [pg. 138 and 168-169]:

“It was in vain that orders were given for all who refused to abandon private feuds and to settle their quarrels in a court of law to be sent to the king’s palace, where they might expect to be punished by banishment to another part of the kingdom. Not even the general oath of fealty imposed by Charles contained a general prohibition of feuds. Instead the government contented itself with prohibiting the carrying of arms ‘within the fatherland’, and with setting up courts of arbitration with the possibility of appeal to the tribunal of the palace. But as far as the prohibition of carrying arms was concerned, not even the clergy were inclined to obey it. The lesser vassals who were themselves hardly in a position to conduct a feud, could always induce their lords to interfere in their quarrels by invoking their right to protection…. But not even the most primitive form of private warfare, the blood feud, actually died out. On the contrary, it appears to have flourished especially among the lesser nobility and the stewards of large domains….

“Just as a lord could force a serf against his will to become a secular priest, so also he could force him to take the tonsure of a monk….

“It certainly suited the secular authorities to rid themselves in this way of opponents or of those involved in a blood feud. In the case of a man involved in a blood feud, however, there was always the danger that the family of the victim would turn their ancient right of revenge against the whole convent.”

and then the carolingian empire broke apart, and all h*ll broke loose (until the capetians gained control of the area we now know as france, and even then it took some time for the kingdom of france to be fully consolidated). various authorities — the church and different barons, etc. — did try to bring peace to the land, but it really didn’t work for very long, if at all. from the wikipedia page on the peace and truce of god:

“The Peace and Truce of God was a medieval European movement of the Catholic Church that applied spiritual sanctions to limit the violence of private war in feudal society. The movement constituted the first organized attempt to control civil society in medieval Europe through non-violent means. It began with very limited provisions in 989 AD and survived in some form until the thirteenth century.”

interestingly, the peace and truce of god movement began in southern france, not in the north where The Outbreeding Project had began earliest. perhaps those populations in southern france experienced more feuding in the late-900s than in the north? i don’t know. don’t have any direct proof (yet). in Medieval French Literature and Law (1977) we learn that everyone — the church, the lords of manors, the kings — tried EVERYthing they could think of over the next three to four hundred years to stop the feuding, with, as we shall see, very limited success [pgs. 108-113 and 116 – long quote here]:

“Direct opposition to the blood feud began to make itself felt in southern France toward the end of the century. Combining ideology with expediency, the horror of blood with a desire for clerical immunity from attack, the Council of Charroux (989) ratified a special treaty of protection. Under God’s Peace, or the *paix de Dieu*, acts of violence against church property, laborers, peasants, their livestock, and clerics were forbidden under pain of official sanction. The Peace of Charroux took the form of voluntary submission rather than true prohibition and was sponsored by local prelates with the cooperation of the local nobility. It must have been at least partially successful, for similar accords were adopted by the Council of Narbonne in 990 and that of Anse in 994. An agreement concluded at the Synod of Puy (990) extended the protection of God’s Peace to merchants, mills, vineyards, and men on their way to or home from church. Pacts of ‘justice and peace’ were signed in 997 by the Bishops of Limoges, the Abbot of Saint-Martial, and the Bishop and Duke of Acuitaine. It was decided at the Council of Poitiers in 1000 that all infractions pertaining to *res invasae* would henceforth be settled by trial rather than war.

“Monarchy favored the ecclesiastical peace movement. It appears likely, even, that Robert the Pious attempted to promulgate a declared peace at Orleans in 1010, although he remained unable to enforce it. By the third decade of the eleventh century the spirit of the southern pacts had spread to Burgundy and the North. At the Council of Verdun-le-Doubs (1016) the lay aristocracy of the region promised, in the presence of the archbishops of Lyon and Besancon: (1) not to violate the peace of sanctuaries; (2) not to enter forcefully the *atrium* of any church except to apprehend violaters of the peace; (3) not to attack unarmed clerics, monks, or their men; (4) not to appropriate their goods except to compensate for legitimate wrong inflicted. The Council of Soissons adopted an identical formula in 1023, as did the Councils of Anse in 1025, Poitiers in 1026, Charroux in 1028, and Limoges in 1031. Elsewhere, the bishops elicited individual promises of nonviolence from members of a particular diocese. At the request of the Abbot of Cluny and in the presence of the archbishop and the high clergy of the region of Macon, numerous Burgundian nobles swore in 1153 to refrain from attacking church property, to resist those who did, and to besiege the castles to which they withdrew if necessary.

“A variation of the *paix de Dieu* was concluded by the bishops of Soissons and Beauvais. The *pactum sive treuga*, or *treve de Dieu*, forbade violence not according to the object of attack, but according to its time, season or day. Wars of vengeance were initially prohibited during the seasons of Easter, Toussaint, and Ascension. In addition to their oath governing sacred property and clerics, the subscribers of the Council of Verdun-le-Doubs swore: (1) not to participate during certain periods of the year in any military expedition other than that of the king, local prelate, or count; (2) to abstain for the duration of authorized wars from pillaging and violating the peace of churches; (3) not to attack unarmed knights during Lent. The Council of Toulouse added certain saints’ feast days to the list of proscribed dates; the bishops of Vienne and Besancon included Christmas and the Lenten season. Caronlingian interdiction of the blood feud on Sundays was revived by the Synod of Roussillon in 1027. From Sunday it was gradually extended to include almost the entire week: first from Friday at vespers to Monday morning and then from Wednesday sundown to Monday….

“The seigneurial peace movement in the large northern feudatory states, themselves large enough to be governed as small kingdoms, prefigured any sustained monarchic attempt to control private war. An accord ratified in Flanders at the Council of Therouanne (1042-3) regulated the right of the Flemish aristocracy to bear arms; the count alone could make war during periods of prescribed abstinence. Angevine Normandy, inspired by the Flemish example, was sufficiently advanced administratively and judiciallys to serve as a model for Philippe-Auguste after royal annexation of the duchy in the early thirteenth century. The *treve de Dieu* signed in Caen in 1047 had validated the principle of ducal regulation of private campaigns. According to an inquest conducted in 1091 by Robert Curthose and William Rufus, William I had enacted, as early as 1075, a *paix de Duc* limiting blood feuds and placing numerous restrictions upon the conduct of any but his own expeditions. The *Donsuetudines et Iusticie* of the Conqueror prohibited seeking one’s enemy with hauberk, standard, and sounding horn; it forbade the taking of captive and the expropriation of arms, horses, or property in the course of a feud. Burning, plunder, and wasting of fields were forbidden in disputes involving the right of seisin. Assault and ambush were outlawed in the duke’s forest; and, except for the capture of an offender in *flagrante delicto*, no one was to be condemned to loss of life or limb without due process in a ducal court. William’s law thus reflects a double current in the control of wars of vendetta. On the one hand, it limits the methods of private campaigns without prohibiting them altogether. On the other, it reserves jurisdiction over certain cases of serious infraction for the duke’s own court, thus bypassing the local seigneurial judge who would ordinarily have enjoyed exclusive cognizance over the crimes committed within his fief….

“Although unable to control the *faida* [blood feud – h.chick] with any certainty until well into the thirteenth century, the Crown did support a number of measures restricting the right to war. According to Beaumanoir, only noblemen can legally settle a dispute through recourse to arms; a conflict between a nobleman and a bourgeois or a peasant was to be resolved in public court. Brothers and even stepbrothers were prohibited from fighting each other. Furthermore, the Bailiff of Clermont carefully defines the limits of family obligation in pursuit of blood feuds. Duty to one’s kin-group had formerly extended to the seventh degree. Beaunamoir maintains that since the Church had set impediments to marriage only at the fourth degree, kinsmen of more remote paternity were not obliged to come to the aid of distant relatives. Thus, while the collective responsibility of the feudal *comitatus* had not been eliminated entirely, it was curtailed somewhat.

“The rules pertaining to initiation and cessation of hostilities were a crucial factor in the limitation of vendetta. As Beaumanoir specifies, fighting may begin either by face-to-fact challenge or by messenger. In both cases the declaration must be made clearly and openly; war without public defiance is the equivalent of murder without warning, or treason…:

“‘He who wishes to initiate war against another by declaration, must not do so ambiguously or covertly, but so clearly and so openly that he to whom the declaration is spoken or sent may know that he should be on his guard; and he who proceeds otherwise, commits treason.’ (Beaumanoir 2: 1675: 358).

“Once war had been declared, the parties had to wait forty days before actually coming to blows in order to alert those not present at the original declaration. This waiting period or *quarantaine le roi*, which was attributed to Philippe-Auguste and renewed by Saint Louis, again emphasizes the distinction between open and secretive homicide; it broadens the criminal concept to cover the domain of general warfare. Surprise attack upon an enemy clan prior to the end of the forty day injunction constituted an act of treason as opposed to legitimate vengeance….”

“The persistence of wars of vengeance following the Saint-King’s death is apparent in the large number of *treves* concluded in the Parlement of Paris during the reign of Philip the Bold [1363-1404]. Despite the attempt to continue his father’s policy of suppression, Philip remained more capable of terminating conflicts already under way than preventing the outbreak of new wars. Philip the Fair experienced even greater difficulty in controlling the resurgence of independent military ventures among his vassals….”

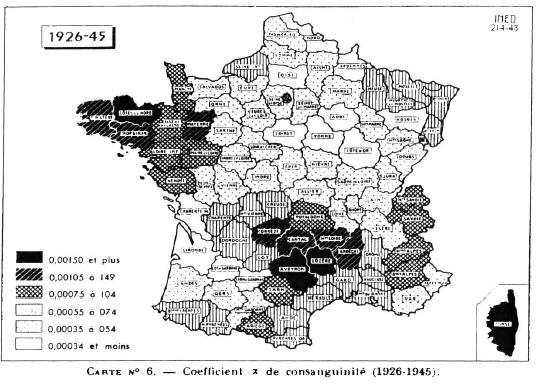

so despite ALL of those efforts from the authorities in medieval france over the course of three or four hundred years, kindred-based blood feuds continued in france until the 1200-1300s. meanwhile, in southern england (but NOT in northern england, wales, or the highlands of scotland), feuding seems to have died a natural death by the 1100s. it would be interesting to know if there were regional differences in the timing of the cessation of feuding in france (like in britain) — my bet is yes, but i don’t have any info on that one way or the other. i will certainly be keeping an eye out for it.

_____

there are some hints, though, that the kindred was, in fact, becoming less important in medieval france before the 1200-1300s.

the first was the increasing significance of the paternal lineage (la lignée) at the (both literal and figurative) expense of the extended family. the nuclear family became more important, and parents (fathers) began to bequeath their wealth and property to their sons (and daughters) — mainly to the eldest son, of course — rather than also to their own brothers and cousins and second cousins thrice removed (you get the idea). as i wrote about in a previous post, this process of the shrinking and verticalization of the french family began around ca. 1000. most of the historical data we have on this process comes from the northern/austrasia region of the franks — where The Outbreeding Project began — but that doesn’t rule out that it wasn’t also happening elsewhere in france. again, i’ll have to keep my eye out for more info.

another indicator of the decreasing importance of the kindred in medieval french society, imho, is the rise of the communes (liberté! egalité! fraternité! (~_^) ). (yes, i know there were communes in northern italy, too. i’ll come back to those at a later date.) the later communes in medieval france — in the 1100-1200s — tended to be officially established entities given charters by the king or some regional lord, but the earliest ones from the late 1000s were really movements — associations — “of the people” — of individuals (and maybe their immediate families), NOT of whole kindreds or clans or tribes. from Medieval France: An Encyclopedia (1995) [pgs. 464-465]:

“Communes were sworn associations of rural or urban dwellers designed to provide collective protection from seigneurial authority. The earliest development of self-governing cities occurred in the later 11th century between the Loire and the Rhineland, as well as in northern Italy…. The urban territory became officially a ‘peace zone.’ Responsibility for enforcing order and judging violators fell to the commune, as did collection of taxes and the payment of dues to the king or local lord. These urban franchises were available to all residents, including those who, fleeing servitude in the countryside, remained for a year and a day….

“Communes engaged all inhabitants in a communal oath, thus substituting a horizontal and egalitarian form of association for the more traditional ones of the aristocracy. Within the commune, each member was subservient to the other as a brother. On the ideological level, the notion of ‘peace’ played so fundamental a role that in some charters *pax* and *communa* are synonymous terms….

“Communes continued to form through the 12th and early 13th centuries, and in the reign of Louis IX there were over thirty-five of them in the regions directly north of Paris. They gradually became more established, with a hierarchy of guilds structuring relationships between segments of the population, often concentrating authority in the hands of a clique of ruling families. Communes began to decline after the 13th century, with European economic growth generally….”

the citizens of communes tried their hand at stopping blood feuds, too. most of the commune citizens themselves dealt with disputes with others NOT via the feud and with the help of other family members, but as independent individuals via civil means. however, the commune members might wind up suffering collateral damage if feuds raged nearby, so they tried to put a stop to them. from Medieval French Literature and Law (1977) [pg. 110]:

“Municipal opposition to private war accompanied the communal movements of the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Though theoretically excluded from participating in the blood feud and protected by local peace pacts, the merchants living in northern and eastern France were nonetheless subject to the ravages of vendetta. An abundance of evidence indicates a willingness on the part of some municipal residents to settle their differences independently of civil procedure. Most, however, sought more regular means of settlement. When it came to handling arms, the merchant, like the cleric, found himself at a distinct disadvantage. The commune was, in essence, a peace league, a specially designated civil space whose inhabitants were guaranteed the right to trial without combat. Among the founding principles of the municipality of LeMans (1070) were the repression of vendettas among the members of the urban ‘friendship’ and mutual protection against external attack. The charter of Laon (1128) was entitled to *institutio pacis*; that of Tornai, *forma pacis et compositionis*. The pact of Verdun-le-Doubs was, in effect, an earlier version of the twelfth-century *convenance de la paix*, a protective agreement organized by artisan and trade guilds. In 1182 a carpenter from Le Puy founded a brotherhood of merchants and manufacturers devoted to the suppression of violence. Not only were feuds prohibited within the group, but when a murder did occur, the family of the victim was expected to seek reconciliation with the guilty party by inviting him to its house. The peace league of Le Puy had spread throughout Languedoc, Auxerre, and Berry before seigneurial uneasiness with institutional restraints upon the right to private war led to its own suppression. In spite of constant and often violent opposition, similar *confreries de paix* appeared in Champagne, Burgundy, and Picardie under Philip the Fair and his sons.”

the communes of the 1000-1100s, then, are free associations of independent individuals, usually minus their extended families/kindreds, but plus lots of civic behavioral patterns like the presence of the right to a trial in a court of law rather than the vendettas and feuds of a clan-based society. that’s a big change. wrt timing, the french communes — as free associations of independent individuals in place of kindreds — appear right around the same time as the gegildan in southern england (900s), the gegildan being another type of association of independent individuals replacing the earlier kindreds. again, i’d love to know if there were any regional differences in where these communes were located (apart from between the loire and rhine) — more in the north? more in the south? i shall endeavor to find out.

_____

tl;dr:

to sum up, then — the pre-christian franks, like all the other pre-christian germanics, were a cousin-marrying, kindred-based population in which the extended-family was extremely important (on top of the nuclear family) and in which blood feuds between kindreds regularly occurred. a frankish individual’s identity was all bound up with that of his kindred — frankish society was not comprised of independently acting individuals. feuding also took place amongst the romano-gauls, so they were likely clannish, too.

the roman catholic church banned cousin marriage in 506, but it’s likely that the franks didn’t take this seriously until after the mid-700s (although the particularly devout may have), at which point they really did (see previous post).

beginning in the 1000s, there are indications — the rise of lineages and the appearance of communes — that the french kindreds were starting to break apart. however, feuding continued in france into the 1200-1300s, so clannishness did not disappear in france overnight.

all of this can be compared to the southern english whose kindreds began to drift apart in the 900s and where feuding seems to have disappeared by the 1100s. remember that the law of wihtred in kent outlawed cousin marriage sixty years (two generations) before the franks did. also keep in mind that there may be regional differences in france (as in britain) that might be obscuring an earlier disappearance of kindreds/clannishness in “core” france. or maybe not. we shall see.

whew! that is all. (^_^)

previously: whatever happened to european tribes? and kinship, the state, and violence and mating patterns of the medieval franks and la lignée and the auvergnat pashtuns and the importance of the kindred in anglo-saxon society

(note: comments do not require an email. vive la commune!)