this is just a preview of a post that i’m working on — one on which i unfortunately have not made much headway, mostly because there’s an awful lot out there available to read on the topic (which is a good thing!). i promise, though, that — whenever it does materialize — that post will be a rip-roaring tale of medieval action and adventure! a thrilling and suspense-filled bodice ripper dealing with the themes of passion and madness! good versus evil! violence and punishment! swashbuckling pirates and….

no, wait. hang on a second. that’s not right.

no. as i mentioned in the last post, i’ve been reading up on violence (homicide) and the death penalty in medieval england to see if there exists any evidence to support the perfectly sensible theory that the removal of violent individuals — and, most importantly, their “genes for violence” — from the population in medieval europe (in this case england) resulted in the permanent decline in violence in europe as noted by historians of crime, like manuel eisner, and described by pinker in Better Angels.

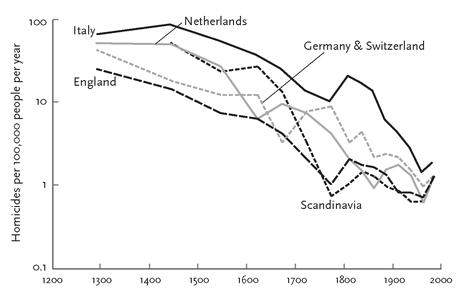

the decline in homicides across europe that began in the middle ages is summarized in this chart from Better Angels (note the logarithmic scale):

the reader’s digest version of what i’ve found out about the death penalty in medieval england so far is:

– over the course anglo-saxon period (which isn’t actually covered by the above chart), the death penalty did come to be more widely applied to cases of homicide, but for most of the period there weren’t really very many executions of killers. in fact, the nascent state (such as it was during this early period) was more concerned about applying the death penalty in cases of theft rather than murder or manslaughter. for most of this period, murder was still avenged by the deceased person’s kindred, either in the collection of wergild or via the good old blood feud. this did begin to change by the tenth and eleventh centuries as more laws that included the death penalty for killings were issued, but even in these later centuries the archaeological evidence suggests that few executions actually happened.

– more laws demanding the death penalty (or castration) for killings were issued and enforced during the anglo-norman and angevin periods, especially as the centralized state became stronger and began to exercise greater control throughout england. one funny thing, though — jury trials were more or less invented during this period (the jury was more of an investigative body, though, like a grand jury rather than twelve angry men passing judgement), and it turns out that the juries tended to be a bit reticent about applying the laws too harshly, so executions actually remained comparatively low during large parts of the norman period. i think you can see this in the trend line on pinker’s graph — homicides do decrease from about 1300 to 1500, but the decline is not super steep.

– the tudor period. as far as i can tell, criminals were executed right and left during the tudor period. the use of capital punishment really ramped up during the 1500s. regional (county-wide) figures from the period show that, depending on time and place, anywhere from 27-50% of felons were executed. and, as you can see on pinker’s chart, the decline in homicides begins to decline sharply after around 1600.

that’s all i’ve got so far, but i’m pretty convinced that the idea that violence declined so much and with such rapidity in the medieval period in england (and the rest of europe?) is at least partly related to the fact that violent individuals were simply removed from the population — and it must’ve been done generally early enough in their careers to stop them reproducing — or slow down their reproductive rates enough that the population was pacified.

don’t think this is the whole story, though. the argument of the population being pacified thanks to the application of the death penalty by the state — by “leviathan” — doesn’t really seem to work fully or for all parts of europe. here is eisner on the differences between what happened in northern medieval europe versus medieval italy [pgs. 127-129 – pdf]:

“Strangely one-sided in respect to the role of the state as an internally pacifying institution, Elias almost exclusively emphasizes the state’s coercive potential exercised through the subordination of other power holders and bureaucratic control. Echoing the old Hobbesian theme, the decline in interpersonal violence should thus develop out of increased state control. Although the long-term expansion of the state and the decline of lethal violence appear to correlate nicely on the surface, a closer look reveals several inconsistencies. Muchembled (1996), for example, points out that the decline of homicide rates in early modern Europe does not appear to correspond with the rise of the absolutist state. Rather, he argues, the example of the Low Countries shows that homicide rates declined in polities where centralized power structures never emerged and the political system much more resembled a loose association of largely independent units. Neither does intensified policing nor the harsh regime of public corporal punishment, both probably the most immediate manifestations of state power in any premodern society, seem to aid understanding of the trajectories into lower levels of homicide rates. Police forces in medieval and early modern Italian cities were surprisingly large — Schwerhoff (1991, p. 61) cites per capita figures of between 1:145 and 1:800 — but they did not effectively suppress everyday violence. Furthermore, no historian seems to believe that the popularity of the scaffold and the garrote among sixteenth- and seventeenth-century European rulers decisively reduced crime.

“Rather, the Italian case exemplifies a more general problem. For whatever the deficiencies of early modern Italian states may have been, they were certainly not characterized by a lesser overall level of state bureaucracy and judicial control than, for example, states in England or Sweden during the same period (see, e.g., Brackett 1992). England was not centralized in bureaucratic terms, and the physical means of coercion, in terms of armed forces, were slight (Sharpe 1996, p. 67). The mere rise of more bureaucratic and centralized state structures thus hardly seems to account for the increasingly divergent development of homicide rates in northern and southern Europe. Examining Rome, Blastenbrei (1995, p. 284) argues that the divergence may, rather, be related to the evolution of different models of the relationship between the state and civil society. While northern European societies were increasingly characterized by a gradually increasing legitimacy for the state as an overarching institution, the South was marked by a deep rupture between the population and the state authorities. In respect to state control, Roth emphasizes a similar point when examining the massive drop in homicide rates in New England from 1630 to 1800: ‘The sudden decline in homicide did not correlate with improved economic circumstances, stronger courts, or better policing. It did, however, correlate with the rise of intense feelings of Protestant and racial solidarity among the colonists, as two wars and a revolution united the formerly divided colonists against New England’s native in habitants, against the French, and against their own Catholic Monarch, James II’ (2001, p. 55).

“Both Roth and Blastenbrei emphasize, from different angles, a sociological dimension whose importance for understanding the longterm decline in serious violence has not yet been systematically explored, namely, mutual trust and the legitimacy of the state as foundations for the rise of civil society. Both are, of course, clearly to be distinguished from the coercive potential of the state — strong states in terms of coercion can be illegitimate, while seemingly weak states may enjoy high legitimacy. And on the level of macro-transhistorical comparison, the decline of homicide rates appears to correspond more with integration based on trust than with control based on coercion.“

yeah. and y’all know what i have to say about all that. (^_^) but i won’t bore you with repeating myself just now — i’ll let you go enjoy the easter holidays. stay tuned for more on this in the near future!

previously: outbreeding, self-control and lethal violence and kinship, the state, and violence and more on genetics and the historical decline of violence and

(note: comments do not require an email. sorry, not really any pirates. (~_^) )

Reblogged this on Foolish Reporter's Foolish Thoughts on the Foolish State of Things.

[…] By hbd chick […]

How do Roth and Blastenbrei quantify mutual trust and the legitimacy of the state?

Why no kink at or after 1350? Could it really not matter that the decline of population density, and the radical changes in economic power, had no affect on murder rates? If the answer were to be “our data are good enough to let us rule out a kink then” that surely is an illuminating fact.

I may be confused by the log scale but doesn’t it show that England had roughly 30 homicides/100K around 1300 that dwindled to 10 around 1500? That seems to be were most of the decline took place even if the curve gets steeper later on.

On the one hand that’s a bit after the Black Death, Staffan. On the second hand, though, I admit I have no idea how one might guess at a reasonable time lag for something like the Black Death to have its influence. On the third hand, if the BD were a big deal you’d expect it to show up for each country, since it affected them all.

@staffan – “I may be confused by the log scale but doesn’t it show that England had roughly 30 homicides/100K around 1300 that dwindled to 10 around 1500?”

hmmmm. yes. i think you’re right (and that i was the one confused by the log scale! (*^_^*) ) thanks.

which makes that sharp decline — between ca. 1300-1500 — even less explicable by the executions explanation. hmmmm.

random thought #1

“Police forces in medieval and early modern Italian cities were surprisingly large”

But were they honest?

“Rather, the Italian case exemplifies a more general problem. For whatever the deficiencies of early modern Italian states may have been, they were certainly not characterized by a lesser overall level of state bureaucracy and judicial control than, for example, states in England or Sweden during the same period”

But did they hang the worst people or the least connected?

===

random thought #2

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coefficient_of_relationship

average relatedness going up?

genetically speaking killing a 1st cousin is four times worse than a 2nd which is four times worse than a 3rd which is four times worse than a 4th (roughly) – so if the average relatedness in a society went up then the cost of murder would go up – not just for the individual concerned but for the whole society.

Purely genetically speaking

if someone who was 8th cousin to you murdered someone who was 2nd cousin to you that would make you very angry

if someone who was 8th cousin to you murdered someone who was also 8th cousin to you that might make you shrug

if someone who was 2nd cousin to you murdered someone who was 8th cousin to you then you might bribe the judge

if someone who was 4th cousin to everyone in your county murdered someone who was also 4th cousin to everyone in your county that would make everyone in the county very angry – nowhere to hide

So a population that went from everyone being 2nd cousin to their clan and 8th cousin to everyone else in their county to one an environment where everyone was 4th cousin to everyone else in the county then a decline in murder would be in everyone’s genetic interests.

-> more honest legal system?

Pinker doesn’t talk about this, nor have I seen it elsewhere, but it isn’t just the murderers being removed from the gene pool; the victims are NOT removed. Thus, there can be a virtuous effect even if few murderers are executed before breeding – if enough murderers are caught and stopped from continuing to kill, the population will contain an increasing number of pacific victim types because they will survive to breed themselves.

Muchembled (1996), for example, points out that the decline of homicide rates in early modern Europe does not appear to correspond with the rise of the absolutist state. Rather, he argues, the example of the Low Countries shows that homicide rates declined in polities where centralized power structures never emerged and the political system much more resembled a loose association of largely independent units.

While not all politics is local, most crime and punishment is. So what matters isn’t whether the king had effective control, but what the local enforcement authority was doing.

Also, if we’re trying to examine violence, one needs to add the homicide rate to the death rate in wars, rebellions, etc.

Neither does intensified policing nor the harsh regime of public corporal punishment, both probably the most immediate manifestations of state power in any premodern society, seem to aid understanding of the trajectories into lower levels of homicide rates. …. Furthermore, no historian seems to believe that the popularity of the scaffold and the garrote among sixteenth- and seventeenth-century European rulers decisively reduced crime.

Historians may or may not believe something – what does the *data* show?

Do you know this blog, chick?

http://tenthmedieval.wordpress.com/2014/04/21/seminar-clxii-feud-and-punishment-in-anglo-saxon-england/

@dearime -“On the third hand…”

That should be “gripping hand”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Mote_in_God%27s_Eye