in Experimenting with Social Norms ensminger and henrich compile several very interesting studies on prosocial “fairness” norms conducted on various populations of different types — ranging from hunter-gatherers to urban factory workers — from around the world. three different economic experiments were conducted on the various populations (although it’s not clear to me if all three were run on each group — i haven’t read through all of each of the studies chapters yet): the ultimatum game, the third-party punishment or altruistic punishment game, and the dictator game.

the authors conclude that [pgs. 89-90]:

“1. Fairness and punishment show both reliable patterns and substantial variability across diverse populations.

2. Fairness increases with a population’s degree of market integration.

3. Fairness increases with an individual’s participation in a world religion.

4. Willingness to engage in punishment increases with community size.”

they ultimately conclude “that social norms evolved over thousands of years to allow strangers in more complex and large settlements to coexist, trade and prosper” — but they just mean that the norms and the cultures evolved, not the peoples.

possible biological/evolutionary reasons for the findings are given some consideration, but only across one and a half pages, and the authors end with the following [pg. 139]:

“Genetic differences between populations or groups would most likely account for the behavioral patterns we observe if they arose in response to stable differences in the culturally evolved social norms and institutions (formal and informal) found in different societies. Norms and institutions, in creating stable regularities in the local social environment, can theoretically produce conditions for natural selection to act on genes that make individuals better adapted to those particular norms and institutions (Henrich and Boyd 2001; Laland et al. 2010; McElreath, Boyd, and Richerson 2003; Richerson et al. 2010). This is an intriguing and provocative possibility, but there is no evidence at this point supporting a suspicion that such a culture-gene coevolutionary process has occurred.”

…and it’s too scary to think about anyway, so we won’t give it any more ink here. (>.<)

in 2010, re. pretty much the same data sets/findings, they had this to say [my emphasis]:

“These findings indicate that people living in small communities lacking market integration or world religions — absences that likely characterized all societies until the Holocene — display relatively little concern with fairness or punishing unfairness in transactions involving strangers or anonymous others. This result challenges the hypothesis that successful social interaction in large-scale societies — and the corresponding experimental findings — arise directly from an evolved psychology that mistakenly applies kin and reciprocity-based heuristics to strangers in vast populations (4,5), without any of the ‘psychological workarounds’ (42) that are created by norms and institutions. Moreover, it is not clear how this hypothesis can explain why we find so much variation among populations in our experimental measures and why this variation is so strongly related to MI, WR, and CS. The mere fact that the largest and most anonymous communities engage in substantially greater punishment relative to the smallest-scale societies, who punish very little, challenges this interpretation.”

this is old school evolutionary psychology at its worst — that human nature and the human psyche (and there’s only one sort in this viewpoint) stopped evolving at the end of the last ice age when a majority of us quit being hunter-gatherers.

well, i’ve got news for them: evolution in humans is ongoing, recent, can be pretty rapid (within some constraints), and has been/is localized (as well as global). in fact, human evolution has sped up since the agricultural revolution since the number of individuals, and therefore mutations, on which natural selection might work skyrocketed in post-agricultural societies.

remember, too, that all human behavioral traits are heritable (and more down to biology than many like to think), “every society selects for something,” and that we’re talking about frequencies of genes in populations and that those frequencies can fluctuate up and down over time.

given all of the above, there are NO good reasons for dismissing genetic or evolutionary explanations for variations in social norms between populations (and individuals for that matter). since we are biological creatures, biological explanations should be ruled out (properly!) first before moving on to other sorts of explanations.

again ensminger and henrich said:

“This result challenges the hypothesis that successful social interaction in large-scale societies — and the corresponding experimental findings — arise directly from an evolved psychology that mistakenly applies kin and reciprocity-based heuristics to strangers in vast populations, without any of the ‘psychological workarounds’ that are created by norms and institutions.”

no, of course not. a more likely scenario is that the behavioral traits realted to social norms in large-scale societies — post-agricultural societies (and post-post-agricultural societies) — evolved with some rapidity away from what had existed before in smaller societies thanks to: 1) the larger population size itself (generating a greater number of mutations), and 2) the larger societies and the structures that developed exerting new selective pressures on those populations in sort-of giant feedback loops — society selects for genes for new behavioral traits which in turn produces new societal forms, and so on.

more from the authors:

“Moreover, it is not clear how this hypothesis can explain why we find so much variation among populations in our experimental measures….”

well, that’s easily explained if you remember that human evolution is ongoing, recent, pretty rapid, and can be local.

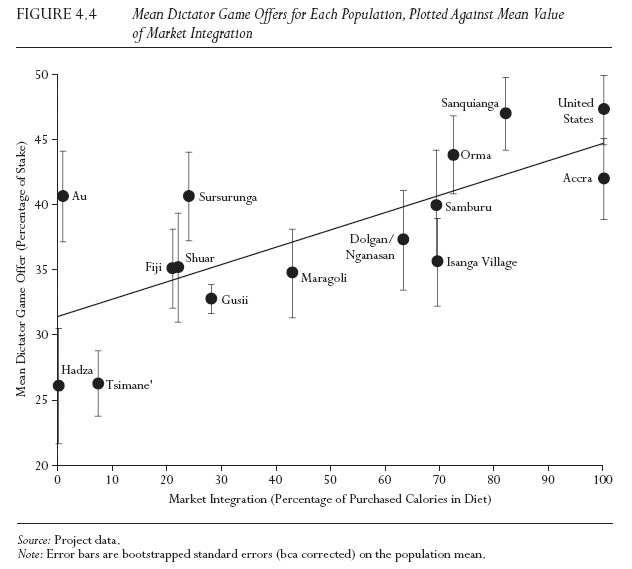

to take just one example from their findings, if we look at their results from the dictator game…

…it was primarily members of the hunter-gatherer or horticulturalist groups who gave low offers in the game, african agriculturalists (or pastoralists) middling offers, and the residents of hamilton, missouri, the highest. (annoyingly, a couple of the populations — accra and isanga — are groups of mixed ethnicities, so it’d be difficult for anybody to tease apart what’s going on.)

well, hunter-gatherers and horticulturalists — like the hadza, the tsimane’, the au, and the sursurunga — have largely missed out on the agricultural revolution and its evolutionary effects. the middling offers from the mostly african (mostly bantu) agriculturalists are not a surprise either since agriculture and the development of large-scale societies got going comparatively late in sub-saharan africa. and that the hamiltonians offered up the most money — and have the highest market integration — probably owes a lot to the fact that that population is a part of the u.s. midlands and are descended from a group that experienced the agricultural revolution back in the neolithic, and furthermore went through the selection pressures created by medieval manorialism and long-term outbreeding (and who knows what else?).

those are just a few ideas for starters. i’m sure it’s much more complicated than that. for instance, why are the tsimane’ forager-horticulturalists so stingy while the au from papua new guinea, who are also forager-horticulturalists, quite generous? i dunno, but one possibility i suggest checking out is the difference in the family structures of the two groups (prolly will be difficult to do this very far back in time): the interconnectedness of au families, which stretch between villages, is quite complex, while tsimane’ families are not so much (afaik). among many other possibilities and scenarios, we should be looking for the selection pressures created by family types and the flow of genes (especially for behavioral traits like altruism) through different family types.

one final thing – ensminger and henrich et al. from 2010:

“Methodologically, our findings suggest caution in interpreting behavioral experiments from industrialized populations as providing direct insights into human nature.”

well, quite. but it works in the other direction, too: we should also be cautious in interpreting behavioral experiments from non-industrialized populations as providing direct insights into human nature(s).

see also: The 10,000 Year Explosion

(note: comments do not require an email. citizens against prosocial behaviors.)